On a hot summer day in 1961, two Black student activists, Kwame “Leo” Lillard and Matthew Walker Jr., decided to go for a swim. They headed to Centennial Park’s swimming pool for whites only.

“They get to the space, and they are turned away. ‘Y’all can’t swim in here today,'” said Dr. Lee Williams of Tennessee State University, recounting their efforts to desegregate the pool.

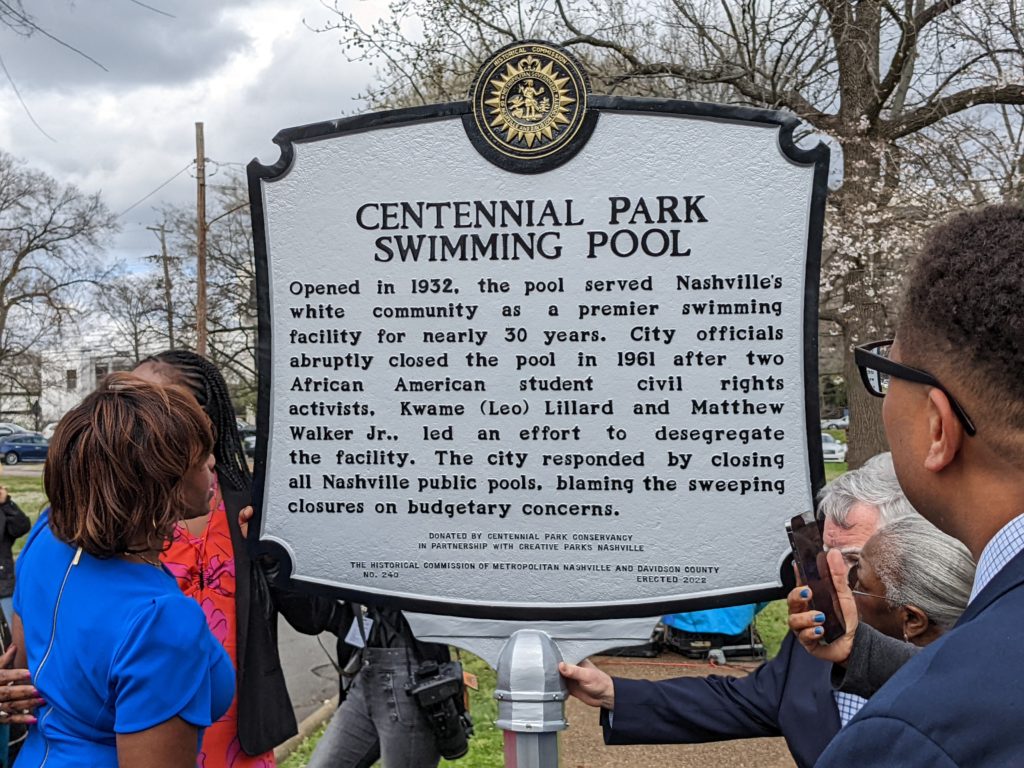

Williams spoke on Wednesday during a ceremony unveiling a new Civil Rights marker memorializing the events of that day in Nashville’s central park.

Following Lillard and Walker’s protest, Nashville responded not just closing the pool, but closing all public pools across the city.

“I thought about what it represented, in that they did not want Black and white bodies being in this sort of intimate space that a pool is,” Williams said.

The city eventually reopened all of its pools except Centennial Park’s, which was later filled in with concrete and covered with grass. The city converted the brick complex nestled at the north tip of Centennial Park into an art gallery in 1972.

The community art hub will celebrate its 50th anniversary next month, but first, Metro officials said it was important to remember its painful past.

“The story behind this location as memorialized by this marker with these careful words … is a painful one, and I suspect most Nashvillians are unaware of this history. But this marker is going to help change that,” said Mayor John Cooper.

Julia Ritchey

Julia RitcheyEvelyn Lillard speaks about her late husband, Kwame “Leo” Leonard, at the unveiling of a Civil Rights marker at Centennial Park on March 23, 2022.

City officials, performers and local Civil Rights activists attended the marker unveiling. Evelyn Lillard, the wife of Kwame Lillard, who died in 2020, also spoke.

She said the marker is a bittersweet reminder of the enduring legacy of the Jim Crow South.

“Why haven’t the authorities figured out a way to have another pool? Do they think they’ll have to clean or get rid of the rainbow of children the next time?” asked Lillard.

Lillard said her husband’s fight was not just for access to a pool but all public spaces, so others could participate and enjoy them for generations.