As President Trump refuses to concede, many in the Republican Party have defended his decision, saying he has the right to ask for recounts. And they point at the 2000 presidential election as an example of the process being normal.

But Roy Neel, who was the director of transition planning for Vice President Al Gore, says the circumstances are not the same.

“The comparison is really only goes so far because in our campaign we were literally — we were literally — only 3,000 votes short,” Neel said.

That election between Gore and Texas Gov. George Bush came down to Florida. One of the central questions was the design of the ballot in a handful of counties and whether they had been tabulated as voters intended. Reviews of the ballots narrowed Bush’s lead over Gore to just 537 votes in Florida, and the U.S. Supreme Court eventually put a stop to the process.

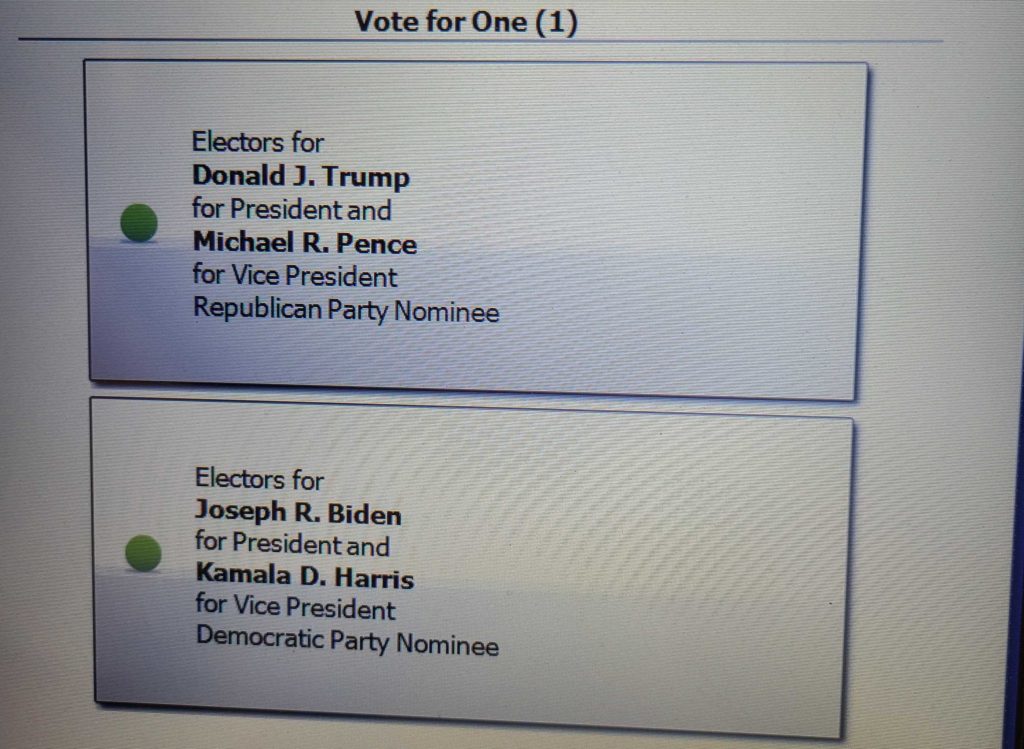

Trump, on the other hand, has claimed widespread voter fraud in multiple states, with no substantial evidence has been provided. President-elect Joe Biden’s lead in those states ranges from 14,000 votes to nearly 150,000.

He has also cast doubts on the counting process, saying early tabulations that showed him leading should be considered the final results, even though they leave out hundreds of thousands of absentee and mail-in ballots that were sent before Election Day.

Many Tennessee Republicans have echoed his complaint, but not all consider a problem. In an op-ed published in Forbes just before the election, another veteran of the 2000 recount, former Tennessee Sen. Bill Frist, called for patience as the ballots are counted.

“With so much at stake, we must take the time to ensure all votes are counted. Whether casting a vote in person or by mail-in ballot, every voice deserves to be heard,” Frist wrote. “There is nothing inappropriate about taking the time to count all votes legally cast, nor is there anything in our electoral laws that requires a winner to be declared on election day.”

Break in tradition

All of this has temporarily saved Trump from making a concession speech. That’s something new, says John Vile, a politicial scientist at Middle Tennessee State University and an expert on concessions.

Take for example John Adams. In 1798 he signed a series of unpopular laws limiting freedoms of speech and the press, as well as making it easier to imprison and deport non-citizens. That cost him the election.

“And he stays home. He didn’t even come to the inauguration,” Vile said. “But he doesn’t question the fact that Thomas Jefferson is the president and that he needs to go home.”

Granted, conceding is not a law. It’s more of a formality, a chivalry which makes the transition smoother. And while not necessary from a legal standpoint, failure to concede could foul up politics for the future.

“Is it worst for the country? Absolutely,” Vile said. “But, are we going to be able to get it through it? Yes, we are.”