Immigrant and refugee households have represented an outsized share of coronavirus cases in Nashville. At one point in June, nearly two-thirds of all new cases in the city came from ZIP codes with large immigrant populations.

But a WPLN News investigation finds that the city is still playing catch-up to provide critical services to contain the spread of COVID-19, especially among Spanish speakers.

Nashville has boasted that it has plenty of contact tracers. However, of the 120 who were brought on early in the pandemic, none of them could conduct an investigation in Spanish themselves. And nuanced conversations are critical to identifying potential contacts and stopping a chain of transmission, like the one that devastated the family of Lenin Tenorio of Madison.

Tenorio and his father both work on construction sites, which have been one of the most common sources of COVID-19 in Nashville. In mid-April, Tenorio got sick with the classic symptoms.

“I felt tired and coughed. I cough a lot because my lungs were infected,” he says in Spanish.

By April 21, he was hospitalized and tested positive for COVID-19. A week later, his mother and father also had to be hospitalized. Even as COVID spread to more family members, Tenorio says he never heard from the Metro Public Health Department.

The Tenorios are among hundreds of immigrant families impacted by COVID-19, and WPLN News finds public health officials have still not overcome key language and cultural barriers with Nashville’s Spanish-speaking residents.

Barriers emerged in mid-April

According to the Nashville health department’s own records, the language barriers were identified months ago.

Courtesy Metro Public Health Department

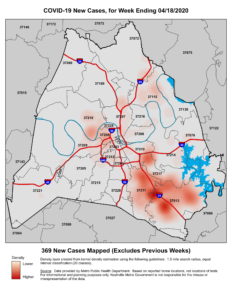

Courtesy Metro Public Health Department This heat map from the week ending April 18 shows new cases of COVID-19 were clustered mainly in Southeast Nashville. The area is home to many Hispanic and immigrant families.

On April 16, Dr. Consuelo Wilkins, who oversees health equity at Vanderbilt, sent a memo to city officials along with a heat map. She warned that many COVID patients didn’t speak much English. Vanderbilt was conducting most of the region’s testing at the time.

“We saw Arabic-speaking people and then this really big cluster of Nepali-speaking people,” Wilkins says. “And then all of a sudden that stopped, and we saw this huge surge of Spanish-speaking people.”

It took nearly three more months after these clusters surfaced for Nashville’s health department to recruit Spanish-speaking tracers. The first four started in early July, and the department says it’s now up to seven.

In the meantime, tracers had been dialing in an interpreter once they realize someone doesn’t speak English. The problem is they usually don’t know whether they’re going to need an interpreter until someone picks up the phone. And that’s because of an unresolved disconnect between testing and contact tracing.

“We collect data on what language they speak at the assessment centers, but there’s no place to capture that in the lab report coming back to us,” says Metro’s deputy health director, Dr. Gill Wright.

Patients fill out a form at testing sites that includes a box for language preference. But that information doesn’t get transmitted when the electronic results come back from the commercial labs.

When a contact tracer calls with those results, they often have to leave a message in English. And if that gets lost in translation, it can throw off the search for who else might be exposed.

Repeated delays

WPLN News also found a series of repeated delays in implementing other services that could have slowed the spread of the coronavirus among immigrant households.

Public service announcements in Spanish-language media only started in July. A Spanish-language hotline staffed by Conexión Américas just launched — five months into the pandemic. And the city still hasn’t followed through on a plan to help immigrant families isolate during their quarantine periods.

Other cities — like New York City, Miami and Chicago — have provided hotel rooms and cash stipends so immigrant patients, who often live in tighter quarters, can isolate while recovering. The cash grants are supposed to help them not feel financial pressure to return to work. Nashville was encouraged to do the same as far back as April.

The health department announced a program at the end of June. But implementation has stalled.

Despite early warnings, Wright says he didn’t really understand the extent of the city’s immigrant clusters until mid-June. But he acknowledges that hiring bilingual staff and implementing new programs has been slow.

“Looking back, yes, we wish we would have added those people quicker,” he says. “But we realize that this is a definite need now. So we can only go forward and improve as we go along.”

‘No excuse’

Courtesy Metro Public Health Department

Courtesy Metro Public Health Department While a hotspot in the city’s urban center has escalated in recent weeks, neighborhoods in Madison and Southeast Nashville, home to many Hispanic and immigrant residents, are still seeing high numbers of active cases.

The hot spot of Southeast Nashville no longer makes up two-thirds of new coronavirus cases in Nashville.

But immigrant advocates have sensed an ongoing lack of urgency from the city’s top leaders — even those who have been working with them on the response. And some hot spots in Davidson County continue to center on neighborhoods home to some the city’s most vulnerable residents.

“There’s really no excuse for not having a response that’s proportionate to the crisis in the immigrant and refugee community,” says Lisa Sherman-Nikolaus, executive director of the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition. “It’s a matter of life and death.”

Dr. Morgan Wills of Siloam Health, which works primarily with immigrant patients, has partnered with the city to hire community health workers to assist with outreach. But he’s imagined what might be different if these persistent hot spots were located in affluent communities, rather than the more working-class neighborhoods of Antioch and Madison.

“I think if that heat map was centered on Green Hills, you’d see a very different response from a lot of people, just by virtue of the power of proximity,” he says.

In Madison, Lenin Tenorio and his father recovered. But his mother never came home from the hospital. They buried her in late June.

“I lost my mom because of this,” he says. “And it’s really just so sad. I never thought this would happen.”

Clarification: This story originally reported that two-thirds of all people who contracted COVID-19 in June were immigrants and refugees, a statistic provided by the Metro Public Health Department. The mayor’s office later clarified that the city tracks people’s ZIP codes but not citizenship status.