The sun is rising over the Haywood County Community Hospital, and Michael Banks looks like he’s shooting a commercial — standing in front of the emergency department entrance in a seersucker suit, greeting employees in the dim morning light.

“Alright, go get your stuff set up. Let’s get ready to rock and roll,” he tells Jeanine Ing, who is leading the hospital’s lab. She started her career in this hospital decades ago.

“No backing out now,” she tells him.

Banks is a local attorney who was chair of the hospital’s community board when it closed in 2014.

“I remember getting called into that office right there by the CEO at the time and him telling me they were closing,” he says, pointing to the executive offices that line the front of the facility. “For this to be opening back and providing services for Haywood County is incredible.”

When a rural hospital closes, it usually closes for good — no matter what the owners say about their hope to reopen. Small towns are often fighting a losing battle against far more powerful economic forces.

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN News Michael Banks, CEO of Haywood County Community Hospital, chats with employees as they await their first patients on Aug. 15. Banks was chair of the local hospital board when the previous owner, Community Health Systems, decided to close the facility.

Haywood was owned by Franklin-based Community Health Systems, a for-profit hospital chain that has tried to get out of the rural hospital sector entirely. The publicly-traded company nearly went out of business because of the squeeze of reimbursement changes in the Affordable Care Act. Former CEO Wayne Smith blamed Republican leaders’ refusal to expand Medicaid, passing up billions in federal funding.

The financial pressure didn’t just hit CHS. In all, 16 rural hospitals closed in Tennessee — more than anywhere but Texas. And none have reopened until now.

“This building sat here for six or seven years with no air circulation, no water in the lines, everything just deteriorates,” says Barry Dunagan, who was head of maintenance before the hospital closed and was given to the local government.

The building invited vandals and gathered graffiti on the hill outside the town square of Brownsville. Dunagan assumed it would be bulldozed.

“It takes a world of work to ever get it back,” he says.

But it’s really happening. And Dunagan has his old job back.

They’re down to installing the door stops and placing trash cans. The building itself is bigger than the community needs at the moment. In the first phase, the new owner, Braden Health, plans to to operate nine beds and then expand to 49, according to its paperwork filed with the state. Right now, the hospital is only operating the rural health clinic attached to its ER as it waits for final licensing approval.

Braden Health acquired Haywood from the local government in 2020 with only a symbolic payment and a commitment to invest in the facility to run it as a hospital. Braden also has three other hospitals between Nashville and Memphis, all taken over since 2020. They include the shuttered Decatur County General Hospital, which is in equally rough shape.

Haywood has proven more challenging than expected. The hospital was supposed to open in January.

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsTerry Stewart of Braden Health explains the effort to save tiles painted by elementary students in Brownsville more than 20 years ago. Hundreds of tiles with paintings and handprints cover the walls of the lobby at Haywood County Community Hospital.

“We started seeing some spots of mold come back up. So we gutted the building again,” says Terry Stewart, who oversees maintenance and construction for Braden Health.

The mold-related tear-out complicated Stewart’s pet project — attempting to preserve hundreds of square ceramic tiles that kids who grew up in Brownsville had painted and put on the walls in the late 1990s and early 2000s. They had to survive a second round of demolition.

“If they just had one crack, I glued them back together and put them back on the wall, just so I could say I saved everything I could possibly save,” Stewart says.

Saving the tiles has become a sort of symbol of Braden Health’s commitment to the community. Throughout construction, Stewart says delivery drivers and garbage collectors would ask to come in and find theirs.

Tyeshia Allen is still looking for her tile.

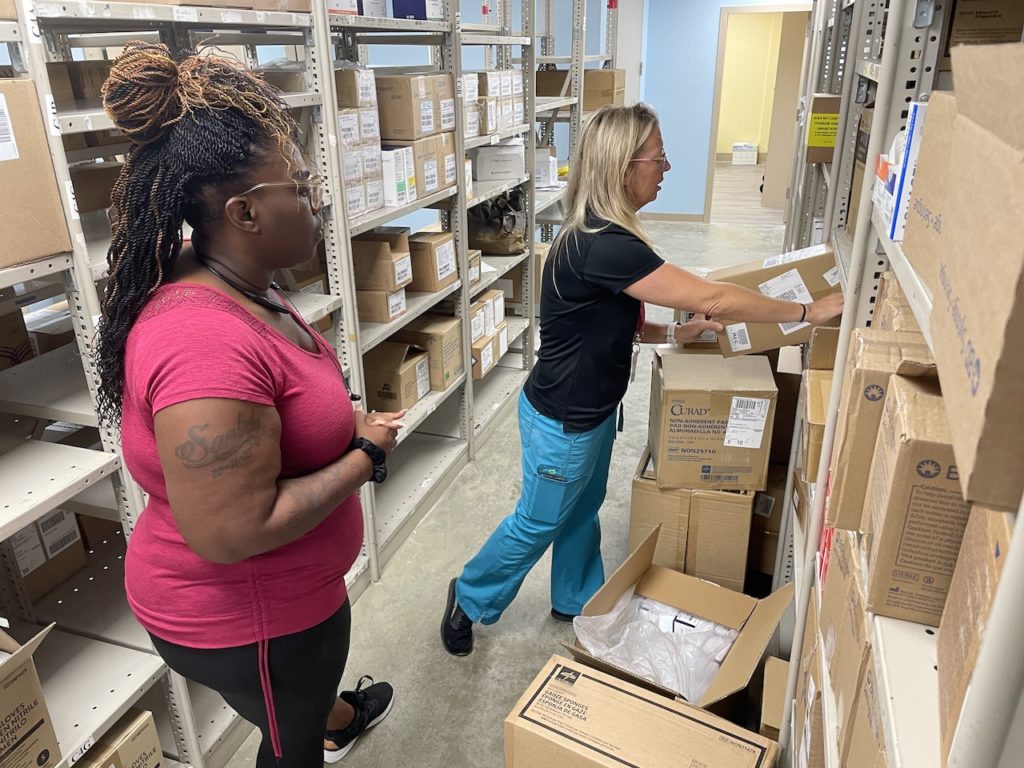

Tyeshia Allen (left) moved back home to Brownsville from Illinois to work at the newly reopened Haywood County Community Hospital, where she is managing the supply room.

“I’m going to find it. I got plenty of time to find it,” says Allen, who is another employee reeled back for the reopening. “When I came in here first, I was like, oh my god, they still have the handprints.'”

Allen moved to Illinois after the hospital closed. She returned to manage the supply room. Now she’s trying to convince other former co-workers to come back too. Several nurses are driving an hour or more to work at other hospitals.

“I’m so excited. This is literally home for a lot of people,” Allen says. “Hopefully we get our family back a little bit.”

Then there are the patients who’ve gotten used to driving to Memphis or Jackson for care. Allen says her mom says she’s going to find a reason to come in during the first week.

It will take time to change habits and rebuild trust. On the first day, which was soft launch, the first patient didn’t show up until mid-afternoon. But Amy Spotts left a satisfied customer.

“My husband drove by this morning and saw the sign out that said it was open, and I called him earlier and said I need to go somewhere,” Spotts says as she’s heading out the sliding doors.

She and her husband didn’t realize they’d be making history, but they became the first patients in Tennessee’s first rural hospital to successfully reopen.

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsSome of Haywood County Community Hospital’s signage is still covered up since it is not yet licensed. But the hospital’s rural health clinic opened Aug. 15.