If the heat has felt particularly brutal this summer, it is not your imagination.

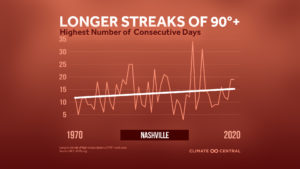

Nashville reached at least 90 degrees for 28 days in a row, during what is now the fifth-longest heat streak on record. On Monday, storms delivered cool water to temporarily break up the heat.

But, the temperatures are expected to climb back up to 90 degrees on Tuesday and remain that high for at least a week.

Halfway in, this summer would be considered the second-hottest on record. On Sunday, the average summer temperature sat at 82.1 degrees. The current record is 82.8 degrees, set in 1952.

“We can definitely say we’re in the running,” said Sam Shamburger, lead forecaster at the National Weather Service in Nashville. But, he says wetter conditions could develop in August and cool things down.

Nighttime temperatures have been warmer than normal, and daily high temperatures have been especially hot. In June, the average maximum temperature was 92 degrees. On Sunday, the average maximum for July was 94.2 degrees. Both are about four degrees warmer than the 30-year average.

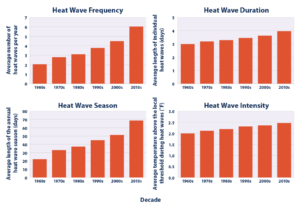

This type of heat can be quite dangerous, despite being an invisible risk. A heat wave is the deadliest extreme weather event, and its frequency, duration, intensity and season is increasing in the U.S. because of climate change, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Animals, plants, soil, water and air — really the entire ecosystem, since it all overlaps — are at threat during heat waves. Animals are at risk for dehydration and can’t recover at night. People can also lose the ability to cool off.

Humans cool themselves when sweat on skin evaporates into the atmosphere, transferring the body’s heat in the process. But the rate of evaporation depends on how saturated the air already is, which is why humidity is such an important indicator in heat safety.

Plants and soil also cool themselves (and ambient air) down by evaporating water, which is one reason why heat and droughts are so interconnected.

Courtesy Environmental Protection Agency

Courtesy Environmental Protection Agency Heat waves are intensifying in the U.S.

Additionally, heat can simultaneously make things drier while also setting the stage for heavier downpours and more severe storms. This is partially because warming is increasing atmospheric concentrations of water vapor, which has been going up by about 1 to 2% per decade, according to the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report.

Heavier downpours are not great cures for droughts, either. When water from rapid rainfalls hits dry ground, it can run off into rivers and streams instead of dampening soils. That, in turn, can cause aquatic die-offs, which heat also impacts.