In the pews of Woodbine United Methodist Church on Wednesday night, dozens of parents and educators chanted, “Our students are more than a test.”

The test they were referencing was the Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program, or TCAP. Specifically, the English Language Arts portion. At the end of this school year, under a new state law, the third graders who score less than proficient on that section could get held back.

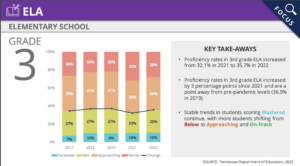

Now, parents and educators are advocating for changes to the law which could put the majority of third graders at risk of retention. In recent years, more than 60% of the state’s third graders have scored “approaching” or “below” proficient on the ELA portion of the TCAP test.

Courtesy Tennessee Department of Education

Courtesy Tennessee Department of Education This powerpoint slide from the state’s Department of Education shows that more than 60% of Tennessee third graders consistently score less than proficient on the ELA section of TCAP.

Pam Wheeler was among the parents at Wednesday’s town hall meeting.

“Right before the holiday break we got the first indicator sent home, and it was ‘Don’t worry… but your student, your kid is at risk,'” she recalled.

Wheeler said her family was surprised at the letter, since her daughter has been earning straight As. She said they’d also been ignorant about the state’s new policy.

School counselor Talesha Simpson said that a lot of kids struggle with test anxiety.

“They can do well doing the class work, homework, regular tests,” she said. “But there’s a difference between testing regular and standardized tests.”

Third grade is also the first time students take standardized tests like TCAP, which parents worry that will add an additional layer of stress.

How we got here

Proponents of the law passed the measure relatively quickly during a special legislative session in 2021 to address pandemic learning loss. At the time, some lawmakers said Tennessee shouldn’t advance students who aren’t meeting standards.

You’ve got to reach a point that we just can’t keep pushing the kids forward,” said Rep. Scott Cepicky, R-Culleoka, during an interview last month.

Students can avoid being held back by going to a summer learning camp, special tutoring — or both. They also must demonstrate growth on their next TCAP exam or could be held back from going to fifth grade.

As implementation of the law draws closer, parents and education officials are questioning whether lawmakers considered all the potential consequences.

Metro Nashville School Board Member Freda Player warned that if a large number of third graders are held back, it could create overcrowding issues.

“That space gets taken up, and then we have to find more space and more teachers and build more portables,” Player said. “It has a ripple effect logistically that they’re not thinking about.”

There are also concerns for racially and economically marginalized students, kids with disabilities, and English learners.

The law contains exceptions for students with disabilities that affect their ability to read. English language learners with less than two years of ELA instruction and kids who’ve already been held back once are also exempted from the law.

Courtney Dial, an English instructor for EL students, said the vast majority of her students received letters warning that they are at risk of retention. She said most of them did not qualify for the exceptions. That’s even though a significant part of their English instruction may have been impacted by COVID.

Other attendees said custody arrangements and transportation could prevent students from participating in the programs that would allow them to go to fourth grade.

Parents are advocating for changes

Parents expressed support for high dosage, low ratio tutoring and the summer bridge camps. But they do not want them to be mandatory. Instead, parents atthe town hall said they wanted local authorities to have the final call on who gets held back. And they want those decision based on more than one test score.

The Wednesday night meeting was the second of two gatherings on the law. The forum was hosted by Statewide Organizing for Community Empowerment and a new group called More Than a Test.

The NAACP and MNPS Parent Advisory Council also held discussions about effect the law could have on students and school systems earlier in the week.

Many of the attendees are hoping to convince state lawmakers to support a bill that would give control over retention back to local authorities. The bill, H.B. 0107, would require school districts to establish their own policies and delay the start of the law to next school year.

Some parents said they planned on attending the House K-12 subcommittee meeting next Tuesday, Feb. 14, for the bill’s first scheduled hearing.