On a sunny day in April, a few dozen applicants hoping to join the Metro Nashville Police Department wait in line to run through an obstacle course and jump over a 4-foot wall. But no one seems that nervous. They’re all too busy laughing at Sgt. Clifton Knight’s corny jokes.

“Slow feet don’t eat!” he yells as they weave through orange cones on the pavement. “Got to have quick feet through those corners!”

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsApplicants at the Nashville Police Academy run through an obstacle course in April 2021.

This is not what the agility test was like when Knight joined the department in 2005. He remembers running up and down a flight of stairs and crawling under obstacles. Then you had to hold a rusty revolver in your weak hand and pull the trigger six times.

“Like, a 50-pound trigger pull,” Knight says with a laugh. He moans, remembering how difficult it was to fire the gun.

But that was nothing compared to the 6-foot wall.

“People couldn’t get over the wall,” Knight says. “So, there are people going home and crying. I will never forget that. Crying and distraught over they couldn’t get over — now they don’t have their chance.”

But it’s not like that anymore. The wall is shorter. There’s no rusty revolver. No flight of stairs.

Applicants still must be in good enough shape to carry a body or chase someone down the street. But the extreme stunts that police would rarely encounter in real life are gone — especially the ones that often weeded people out. These days, the exercises are meant to ensure everyone has a fair chance at getting into the academy.

For years, the Metro Nashville Police Department has struggled to recruit women and people of color. That’s eroded trust with many communities who want officers that look like them. Now, a new administration is making changes at its training academy. They hope the updates will attract — and better prepare — a more diverse set of officers.

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsSgt. Clifton Knight jokes with applicants at a physical agility test at the training academy in April 2021.

“It was definitely time for us to look at what we’re doing,” the sergeant says. “We have an administration that’s like, ‘Yeah, let’s look and see what’s the right choice. How can we open it up so that we’re not discriminating against people and give folks a chance to do this?’ Here’s what we came up with.”

The goal is to get a more diverse group of cadets into the academy — and to make sure that they graduate. Between 2011 and 2020, only about 60% of women and 70% of nonwhite men completed the training program. That’s compared to more than 80% of white men.

Researchers say police academies may need to make some drastic changes to make officers with different backgrounds and perspectives feel welcome.

A different approach to training

“I would hope that every police academy director looks at his or her academy and asks the question, ‘Am I providing the best educational environment I can?'” says Tom Mahoney, a retired criminal justice professor who spent more than two decades in policing in southern California.

In the 1980s, Mahoney researched how police are trained.

Mahoney says it’s not just about what recruits learn at the academy. It’s also about how they learn it. He remembers his own instructors using derogatory language, like calling the people they arrested “dirtbags.”

“Those little, subtle differences in terminology can sometimes affect the way a police cadet or, ultimately, a police officer [or] deputy sheriff looks at the people that they’re interacting with on a daily basis,” he says.

In his report, Mahoney predicted law enforcement agencies would struggle to recruit and retain officers unless they changed their training. He ended his paper with a plea to rethink the authoritarian atmosphere and sent it to every academy director in the state of California. Not a single one replied.

“I think that there’s a hesitancy to change,” Mahoney says.

In Nashville, Deputy Chief Kay Lokey says that’s not the case. She calls the recent graduation rates “disheartening.” For more than a year, Lokey has been working to understand why so few women and people of color are hired into the academy, and why even fewer make it through.

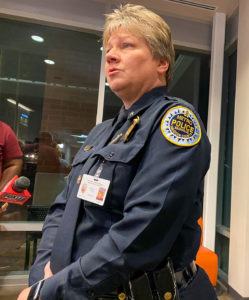

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsThen-Commander Kay Lokey speaks at a press conference in December 2019.

“What we were doing in the past wasn’t really giving us the results that we wanted,” she says.

Lokey says it’s important to attract — and hold onto — those women and people of color. And it’s not just a numbers game. Multiple studies have found those officers tend to use force less often than their white, male colleagues. Research also suggests more diverse departments can improve relationships between officers and the community.

MNPD has created a pre-academy, to help all kinds of recruits get in shape. Cadets are now assigned mentors. And the academy is lowering the stress level, so most training will feel like a college classroom instead of a military bootcamp.

“There are aspects of stress inoculation because we have to. We have to make sure that when you’re out on the street and you get involved in a situation like nothing that you have ever experienced, that you remain calm, you rely on your training and you use the best tactics possible,” Lokey says. “So, we can’t totally get away from any stress factors in the academy, but we can tone it down and only introduce those stress moments when they’re necessary and needed for training.”

Lokey hopes calmer instruction will translate into calmer interactions with the public. She says the ideal candidate isn’t someone who is already super athletic and a master at defensive tactics. It’s someone with integrity.

“I can teach you to drive a police car. I can teach you to fire a weapon. I can teach you the defensive tactics,” she says. “But I can’t specifically give you critical thinking skills, problem solving skills. I can’t teach you how to communicate or how to have empathy when dealing with the public.”

Lokey also wants to see more women at the academy. MNPD has signed onto a national initiative that aims to fill 30% of police recruit classes with women by the end of this decade. Currently, just about 11% of Nashville officers are women.

‘I like my chances here’

“I want girls to know it does not matter what you look like. If you want a man’s job, you can do it,” applicant Lorena Rivera says back at the training academy last April, while catching her breath after a 500-yard run. Today, she’s one of just four women taking the agility test, along with several dozen men.

“Right now, I’m a parking enforcement officer,” says Rivera, who lives in the Chicago suburbs. “I’ve been trying to be a cop for the past three years. Hopefully this is it.”

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsLorena Rivera, right, cheers on fellow applicants at the police academy in April 2021.

Rivera is petite, with big, round glasses and a braided ponytail that falls down her narrow back. She wants to help people. And she loves dogs. She’s hoping to be a K-9 officer.

Rivera has tested at other departments before, without success. She says she’s always surprised to find she’s one of just a few female applicants.

Rivera hopes that helps her chances. Plus, she says, she speaks Spanish. Still, she knows that’s not enough to guarantee her a job on the force.

“Mind you, I don’t have military background. I’m not a male,” she says. “I’ve got obstacles, definitely.”

Rivera thinks those obstacles often deter departments from hiring her.

“They don’t take that chance,” she says. “But it seems like here they want to build a very diverse group. So, I like my chances here.”

Rivera starts tearing up as she imagines getting the phone call to let her know the department wants to hire her. She hopes MNPD is finally ready for someone like her.

This is the third story in a three-part series WPLN News is airing this week about racial and gender disparities in the Nashville police academy. It was produced in partnership with APM Reports. Find all our reporting on policing at wpln.org.

This story was produced as part of APM Reports’ public media accountability initiative, which supports investigative reporting at local media outlets around the country. Support also came from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

This story was produced as part of APM Reports’ public media accountability initiative, which supports investigative reporting at local media outlets around the country. Support also came from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.