The scene in a quiet exam room still makes Victoria Campbell of Nolensville emotional.

“It’s like the dreaded words you never want to hear,” she recalls from the check-up in 2019 during her first pregnancy. “‘I’m sorry. There’s no heartbeat.'”

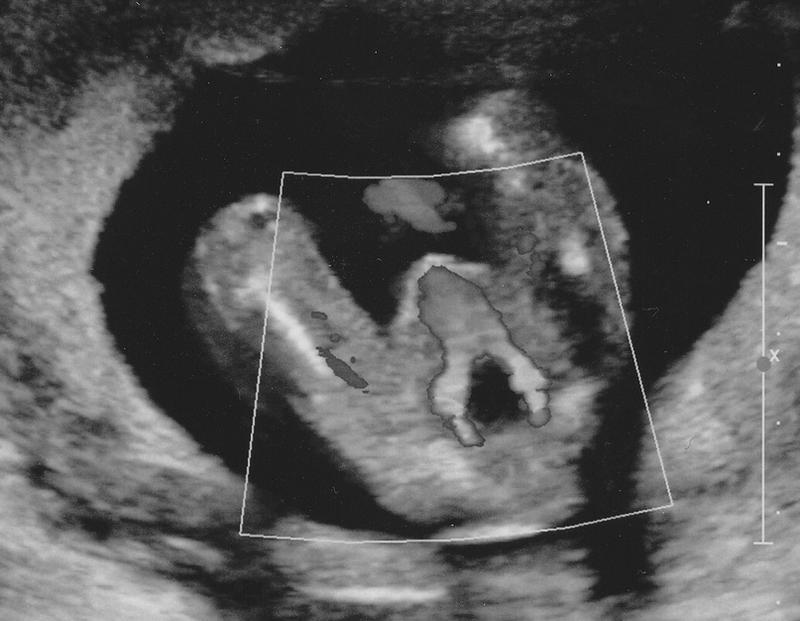

The publishing manager, now 35, was 10 weeks along. She and her husband had already been to their first appointment to confirm the at-home pregnancy test. They were still buzzing from the prospect of being first-time parents.

Campbell was in disbelief. She hadn’t had the cramping and bleeding that usually goes with a miscarriage. The doctor explained that those symptoms would come eventually. After emotions settled, they talked through the options. One was waiting for her body to expel the pregnancy tissue on its own. But that carries a risk of infection, and Campbell felt it would only delay her grieving.

“Just knowing, like, you’re carrying something dead inside of you — that also just seemed terrible,” she says.

The way doctors care for a pregnant person having a miscarriage is very similar to abortion care. In fact, for medical purposes, a miscarriage is considered a “spontaneous abortion.” And it’s the fate of at least one-in-10 pregnancies. So Tennessee physicians are pretty concerned. They say outlawing abortion could also criminalize how they care for other pregnant patients.

Campbell’s other options were a surgical procedure, known as a D&C, to remove the pregnancy tissue, or passing it with the help of medication. Both are virtually identical to elective abortions. They even appear as “abortions” on a patient’s medical chart. Campbell chose the medication, though it meant spending an emotional weekend in the bathroom. Her doctor called in the prescription, and she sent her husband inside the pharmacy to fetch it. He returned to the car distraught.

More: Tell us about your personal experiences and questions surrounding abortion

“The pharmacy tech had made a comment, like, ‘Are you really sure you want to go through with this?’ The thought that somebody could make that assumption, without knowing what the situation was, was really hard to hear in a moment that was already devastating, heartbreaking,” she says.

In a matter of weeks, instead of just an insensitive remark, someone who suspects an abortion would have reason to alert law enforcement. Because unless the patient is dying, an abortion — even by medication — would be a class C felony.

“I just think there are lots of unintended consequences of all of these bans that people tend to be so hyper-focused that they miss,” says Dr. Nikki Zite of Knoxville, who leads the Tennessee section of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. They were not consulted when Tennessee passed its abortion ban in 2019. “The Human Life Protection Act” would be triggered if Roe v. Wade was ever overturned — which now appears imminent.

But even just a few years ago, overturning Roe seemed far off to the lawmakers. The debate over the trigger ban was high level. They weren’t talking to doctors. They were almost exclusively focused on the legal process that would trigger the ban. The only substantive questions related to pregnancy came from opponents who pressed over why rape and incest wasn’t an exception.

In response, Rep. Susan Lynn, R-Mt. Juliet, said the goal was to return to Tennessee’s law before Roe v. Wade granted the right to an abortion in 1973. So it’s a blanket ban.

“It’s updated a little bit, just because so much time has passed,” she said on the House floor just before the final vote in 2019. “But it does match our pre-1972 law that just had an exception for the life of the mother.”

What the discussion glossed over entirely is that since the early 1970s, pharmaceutical companies developed drugs that induce abortions. And those same drugs — mifepristone and misoprostol — are used to manage miscarriages.

The overlap is plain as day to any OB.

“I’m surprised by how many people are surprised … even physicians,” Zite says.

More: How medication abortion works, and what the end of Roe v. Wade could mean for it

On May 11, Tennessee OB-GYNs published a statement directed at state lawmakers expressing their concerns.

“We don’t want to be criminalized for taking care of patients, and we don’t want any OB-GYN to feel like their career, their license, their livelihood is at stake for managing a miscarriage,” Zite says.

Tennessee’s two-page trigger ban does have some wording that suggests removing “a dead fetus,” by medication or procedure, does not qualify as an illegal abortion. But a non-viable fetus isn’t necessarily dead, Zite says.

“There’s a heartbeat, but she’s bleeding and her cervix is open,” Zite says, citing a real scenario. “Can we give her the misoprostol to empty the uterus? Or do we have to wait for there to not be a heart rate? Or do we have to wait until she’s bled enough that she needs a transfusion?”

OB-GYNs say, in their collective statement, they’re “eager to work with state lawmakers” to come up with a solution that doesn’t endanger their patients. It’s unclear — even to them — what that solution would be.