Congressman John Lewis, the civil rights icon who helped integrate Nashville businesses in the early 1960s, has plenty of stories to tell. But for one moment on Saturday, he was left speechless.

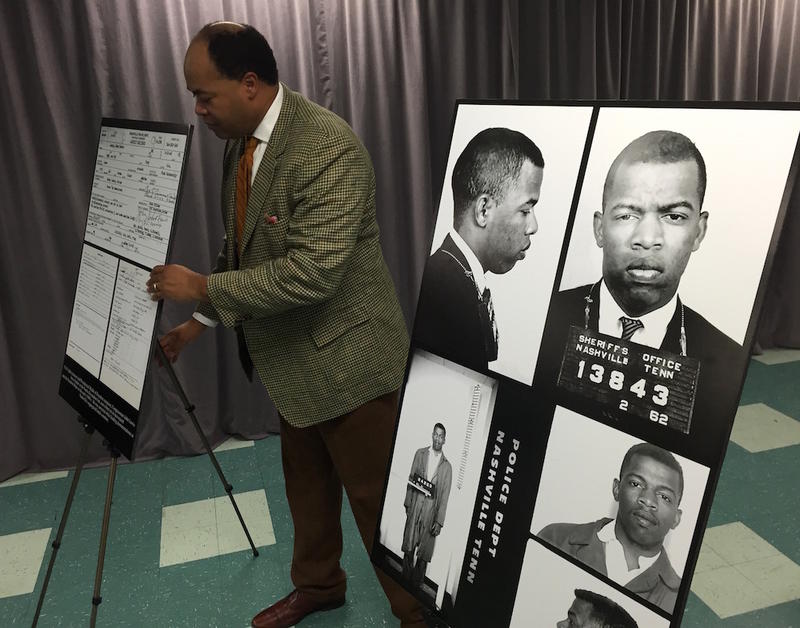

On stage in Nashville in front of a capacity crowd in a high school auditorium, Lewis came face to face with a younger version of himself — a series of Nashville police mugshots from some of the earliest times that his nonviolent protests landed him in jail.

He’d never seen these photos before. Nor had anyone else for decades.

But a local historian’s diligent search — along with a “eureka” moment a few days ago — brought to light the kind of visual proof of Lewis’s fight against segregation that he has often discussed.

“Good trouble,” he calls it — being arrested during peaceful protests against segregation starting in 1960.

“I was surprised, and I almost cried. I held back tears,” Lewis, 76, said after examining the photos. “I was so young. I had all of my hair; and a few pounds lighter.”

He said he’ll display the newly uncovered images in his congressional office, where he has represented Georgia since 1986.

“When young people, especially children come by — and even some of my colleagues — they will see what happened and be inspired to do something,” Lewis said.

In one image from 1961, Lewis stands in a white collared shirt and trench coat. Then, from 1962, he sports a black suit and a skinny tie — the kind of sharp dress that members of

the Nashville student movement wore on purpose when anticipating arrests. Time and again, they headed into dangerous sit-ins at lunch counters and stand-ins outside of movie theaters, both of which became integrated.

City officials also shared enlarged versions of three arrest citations against Lewis, typically for disorderly conduct, with “sit-in” noted, from Feb. 20, 1961; Feb. 10, 1962; and May 4, 1963.

Lewis Got His Start In Nashville

Nashville Mayor Megan Barry made the presentation after Lewis spoke at Martin Luther King Academic Magnet as the recipient of this year’s Nashville Literary Award. He was chosen for the story of his push for equality, as rendered in the graphic novel trilogy, “March.”

“It is clear to me that here in this town, you are beloved,” Barry told Lewis. “You were arrested while you were protesting injustice. You were on the right side of history when the power structure of our community was not.”

Lewis’s

earliest activism began in Nashville, where he learned nonviolent civil disobedience in workshops that trained many future leaders. He would go on to lead the infamous march in Selma, and was the youngest speaker at the March on Washington.

But he still credits Nashville for the formative years.

“It’s here in this city … where I really grew up,” Lewis said in his speech. “I owe it all to this city, and the academic community, and to the religious community here.”

Elusive Photos Show Policing Has Changed

In his personal narrative, Lewis proudly includes a criminal record with more than 40 arrests. A different arrest photo that he

shared on Twitter this summer garnered more than 45,000 shares.

Yet his Nashville rap sheet has long been elusive, says local historian David Ewing. For 15 years, he periodically asked the police to find the records, with no luck.

“I was not hopeful at all,” Ewing said. “I just thought it was one of those things — that they were lost.”

That changed a few days before Lewis’s visit.

Ewing had asked yet again about the records. This time, police spokeswoman Kris Mumford recalled a key detail.

She said that police Chief Steve Anderson recently sought records of Lewis’s arrests to use in a training session. The chief teaches new police cadets about local history at the Civil Rights Room of the Nashville Public Library.

The chief’s intent, officials said, was to show how police treated protesters back then, and to set expectations that they are now expected to allow demonstrators to assemble.

That single paper record included a key archival number on it. And that led back to the police archives. Ewing and Mumford credited police archivist Valerie Wilks for organizing the collection in recent years.

“I remember texting David: ‘Eureka! We found them!’ ” said police spokeswoman Kris Mumford.

The manila envelope, with the name John Robert Lewis handwritten on the flap, included several arrest citations, photo prints and one original film negative.

Listen below to Ewing and Mumford narrating the search for the images.

Ewing said the material will resonate with later generations.

“He’s very proud of what he did,” Ewing said. “He felt this was part of the movement and inspiring people and upsetting the decades-old segregation of lunch counters here in downtown Nashville.”

For Lewis, the photos are proof that change can come from making trouble — which he called the crowd to consider as a duty.

“When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have a moral obligation, a mission, and a mandate,” Lewis said, “to stand up, to speak up and speak out, and get in the way, get in trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble.”