Two days after a bomb erupted in downtown Nashville on Christmas morning, the officers at the scene shared a chilling account of that night.

At a press conference, they described the eery message broadcasting from an R.V., telling them they had just minutes to evacuate the area. The adrenaline rush of racing through buildings and knocking on doors. The orange flames. The loud boom.

Mayor John Cooper called the officers heroes. He said their courage underscored the need to invest in the department.

Rachel Iacovone WPLN News

Rachel Iacovone WPLN NewsA mural from I Believe in Nashville that reads “I Believe in Heroes” was quickly put up outside of the Hard Rock Café in downtown Nashville to honor the six Metro Nashville police officers who evacuated residents in the early morning hours of Christmas Day and potentially saved lives in the bombing.

“We call on our police officers 700,000 times a year to come and help us. This was a super important call that they got today, and they responded very well,” Cooper told WPLN News after a press conference. “So, keeping that response vibrant for us is very important.”

In the days after the explosion, officers were lauded for saving lives, and for working around the clock to investigate the crime.

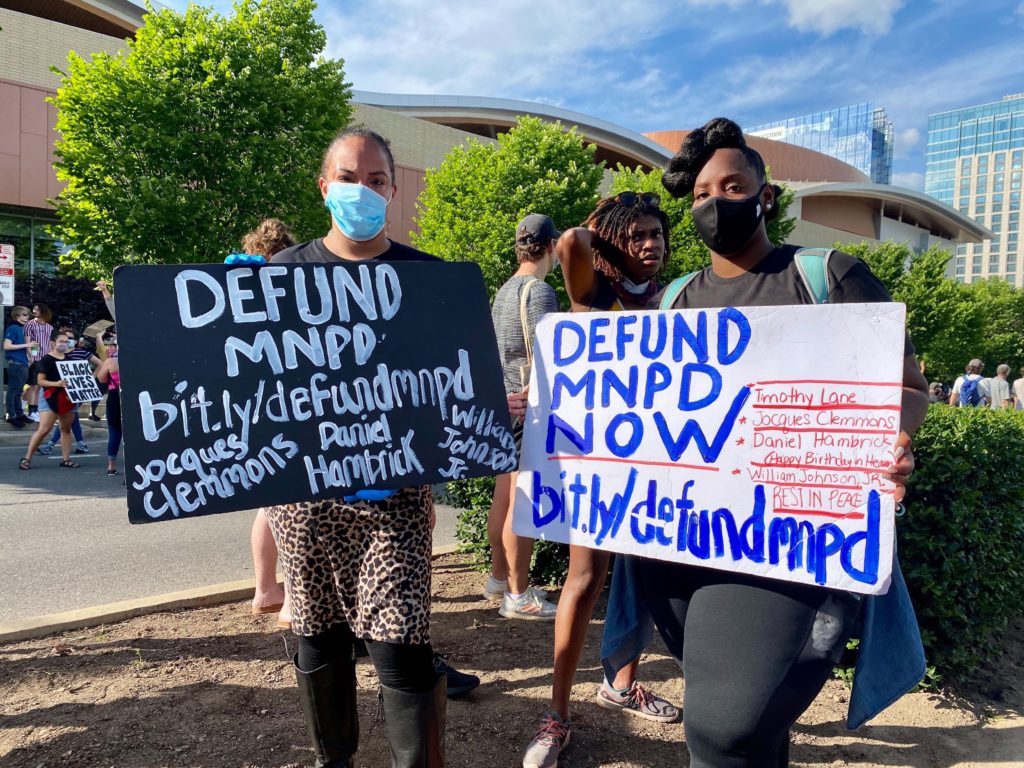

But the celebration of the police department was short-lived. Many activists who urged the Metro Council to cut funding last summer now say the case highlights systemic failures within the police department, and they are as motivated as ever to shift resources.

Four days after the bombing, a report surfaced, showing that officers had been warned in August of 2019 that the Christmas Day bomber was building explosives in an R.V. And they never searched it. They never even talked to him.

The department waited days to share the report with the public. And even then, it struggled to get its story straight.

“Why are we surprised about that?” wonders Theeda Murphy, a local activist with Community Oversight Now and No Exceptions Prison Collective. “It is a consistent pattern.”

Murphy has pushed for police reform for years and has often been met with resistance. She hopes MNPD’s failure to prevent the bombing will finally spur change.

Murphy questions the city’s reliance on police to keep Nashvillians safe, when she says they have failed to do so time and again — from killings of Black men to racial disparities in traffic stops.

“When will people listen? What will it take?” she asks rhetorically, her voice rising with exasperation. “If it doesn’t take a bomb blowing up downtown…what will it take?”

When people like Murphy use the phrase “defund the police,” they’re often accused of embracing lawlessness, or at least making unrealistic demands. But Murphy says she just wants the department to be better. And she says that will only happen if it listens to its critics.

“We all want the same thing, I think,” she says. “We all want the city to be safe. We all want to live in a city that’s safe and prosperous, where we don’t have to be afraid of people blowing up downtown, and we don’t have to be afraid of being robbed when we walk to the store, or any of that kind of thing. We all want that. So, when we criticize the police department, it’s coming from that place.”

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsChief John Drake defends his department’s handling of a 2019 report involving the Christmas bomber at a news conference on Dec. 30.

Police Chief John Drake has repeatedly defended his department’s investigation and says he’s done his best to be transparent about the case. Drake has also created an after-action review committee, comprised of department staff and outsiders, to look for learning opportunities.

“This particular incident, I still say — although we’re looking to see if there was any gaps that existed — I don’t feel like there were any,” he says. “But at least to look at it, have more of a conversation.”

Councilmember Bob Mendes has been pushing the chief to engage in these open, and often fraught, discussions with local lawmakers in recent days.

“We as a city should be able to praise first responders who run into danger and also speak critically about room for improvement,” he says.

Mendes has been one of the most vocal critics of the police department since news broke of the 2019 report involving the bomber, while also steadfastly supporting pay raises for officers.

“As much as people are very, very proud of the police officers who went, again, running toward danger, there’s a legitimate concern out there of, ‘What happened?'” he says. “Police officers were on the property, looking at the R.V., and it’s still an open investigation, and the police department is not able to say what, if anything, has been done after the first week, after the report.”

Mendes doesn’t expect to see any drastic changes to the police budget in the near future. He says emergencies are inevitable. And 2020, with its tornadoes, pandemic, protests and a bombing, put officers on the frontlines of one disaster after the next.

But Mendes encourages people who want money to be reallocated to stay involved in conversations about the budget (a series of virtual discussions about the budget process launched earlier this month and are open to the public).

“Keep talking about it. Show up again this year, hopefully not all night,” he says with a nervous laugh, recalling a seven-hour-long Metro Council meeting when members voted on the budget in June. “Show up as often as possible. You know, government might not move quickly, but it does bend over time.”

Mendes wants the community to have the chance to provide feedback to MNPD. He says even a department that saves lives needs to own up to its mistakes and learn from them.

Samantha Max is a Report for America corps member.