More than 250 years ago, Europeans colonized Tennessee. Farms and houses spread across the land as they cleared forests, prairies and swamps.

Natural features disappeared from maps, perhaps some lost to memory.

By 1971, people demanded conservation for water, and state leaders realized that included wetlands, the saturated soils connecting land and water that support tremendous biodiversity. A year before Congress passed the Clean Water Act, the Tennessee General Assembly set up regulations to protect the system of waterways throughout the state.

For decades, the state ensured no net loss of wetlands in a given year.

“Tennessee was ahead of the federal government at protecting its resources,” Alan Leiserson, a retired attorney with the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation, told WPLN in 2024.

But the state pivoted this year: The Legislature passed a new law to cut protections on vulnerable wetlands — a type called isolated wetlands, which are connected to surface waterways like creeks and rivers through groundwater or ephemeral streams.

Isolated wetlands are scattered across the state, often in the path of proposed construction.

Courtesy Skytec

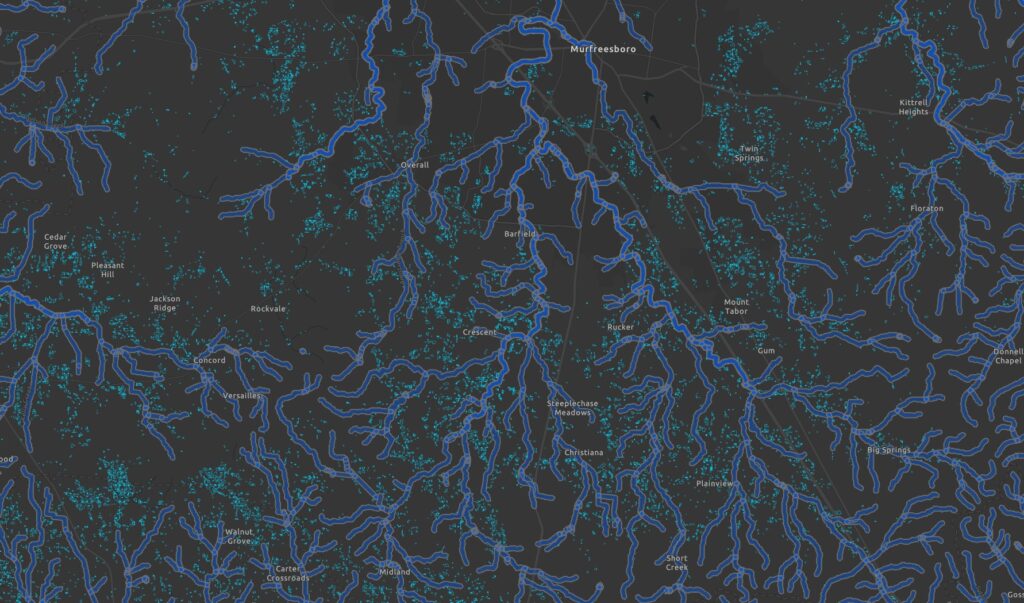

Courtesy Skytec The Duck River watershed houses an abundance of isolated wetlands, represented by small blue dots on the map.

The new legislation removes incentives to build around wetlands and, if building over them, the requirements to pay for mitigating wetlands elsewhere.

“Healthy wetlands are truly critical investments to long-term human and ecosystem health, so this is a devastating blow that they no longer have that protection,” said Grace Stranch, director of the environmental nonprofit Harpeth Conservancy.

How citizens can monitor wetland loss

The law will also make accountability trickier: Developers are no longer required to apply for permits when wetlands are a certain size or type, making it harder for the state to track wetland loss.

Citizens could play a role in this accountability, however, both in where they choose to live and monitoring flood impacts from new developments.

“People in Tennessee can decide where they want to buy their land and property, and developers can decide how they want to build and how they want to show up in the community,” Stranch said.

The state set up a public database for wetlands early this year. The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation hired a consultant to map all likely wetlands, including roughly 320,000 acres of isolated wetlands.

If people are buying a home built in 2025 or later, they could check for historic wetlands, similar to using Google Street View to see if a property had trees before construction.

If an area starts to see unusual flooding, folks can look at nearby developments — as wetlands loss can increase flooding, and that loss does not have to be in the immediate vicinity.

“As long as it’s upstream of you, in the watershed, a reduction of it is likely to have an impact on you,” Justin Murdock, a professor of ecology at Tennessee Tech University, told WPLN in early 2025. “As you fill in more and more, there’s a cumulative effect that then starts to really have a large effect of the water not staying on the landscape as much.”

Wetlands are conservatively estimated to be worth about $50,000 per acre, primarily because they can capture and store significant amounts of water. Midwestern homeowners collectively save billions each year due to the natural flood defenses of wetlands, according to a report by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Courtesy National Park Service

Courtesy National Park Service Wetlands are vulnerable to urban development.

Many scientists, environmental experts and state officials opposed the legislation to remove protections, which was introduced in 2024. It was supported by other legislators tied to the construction industry and eventually sent to summer study after multiple officials weighed in.

“If we’re not having to study it, we’re not having to permit it, I don’t know that we would know what the effects are until it’s too late and until we see flash flooding,” Alex Pellom, chief of staff at the Tennessee Emergency Management Agency, said during a hearing in 2024.

The legislation was sponsored by Rep. Kevin Vaughan, R-Collierville, who works in real estate in West Tennessee. Some years ago, he was associated with a development the state fined for illegally draining a wetland.

“There are resources that need to be protected, but I’ll tell you what doesn’t need to be protected,” Vaughan said, referring to isolated wetlands.

State officials and stakeholders held meetings between May and August of 2024. Vaughan did not attend any of the meetings. He then reintroduced his bill and passed an amended version in 2025. State agencies were notably absent when the legislation resurfaced.

Developers may benefit, but communities could suffer losses

Now, Vaughan and others could financially benefit from the law he championed.

He made an argument that it would make housing more affordable, but there is no clear evidence for this idea. A 2007 federal housing study during the George W. Bush administration concluded that wetland regulations contribute to about 0.08% of a total development project cost.

“The only people who we know will benefit from this are private developers, and that wealth will not trickle down to everyday Tennesseans,” Rep. Justin Jones, D-Nashville, said during a hearing in 2025.

Experts have warned there could be unforeseen consequences to the legislation. Wetlands are essentially extensions of waterways, hosting a disproportionately high level of biodiversity, filtering dangerous pollution and affecting water flow, both during floods and drought.

To understand water in Tennessee, regulators need to understand the entire system, Leiserson, the retired attorney, explained in 2024.

“If you cut off what the regulatory scope is, you’re leaving it completely unregulated,” he said.