Three days after thousands of Nashvillians marched through downtown to protest police brutality late last month, something unprecedented happened at a Metro Council meeting: About 200 people called in or braved the pandemic to read speeches in person.

And nearly all told council members they wanted the same thing.

“I’m asking you to defund the police, divest from incarceration,” one said.

“I think that there are so many other things that we can be investing our money in,” said another.

“If we prioritize policing over education, we are saying that it’s more important to punish than it is to build up,” a public school teacher said.

The overwhelming response from citizens was organized by the Nashville People’s Budget Coalition. Organizer Gicola Lane says the group’s goal is to “create a new vision” for the city — one that spends less on law enforcement and more on community services, like schools and affordable housing.

“A lot of people are scared to talk about taking money from the police, the sheriff, the district attorney’s office,” Lane says. “And since a lot of people who are elected are afraid to have those conversations, we know that their constituents are the people that have to push them.”

Calls to “defund the police” have become ubiquitous in recent weeks. But the phrase means different things for different people — from reducing spending on law enforcement to completely abolishing the police department.

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsJason Casale says he would like to see money spent on training and equipping police officers to be reallocated to education and public health.

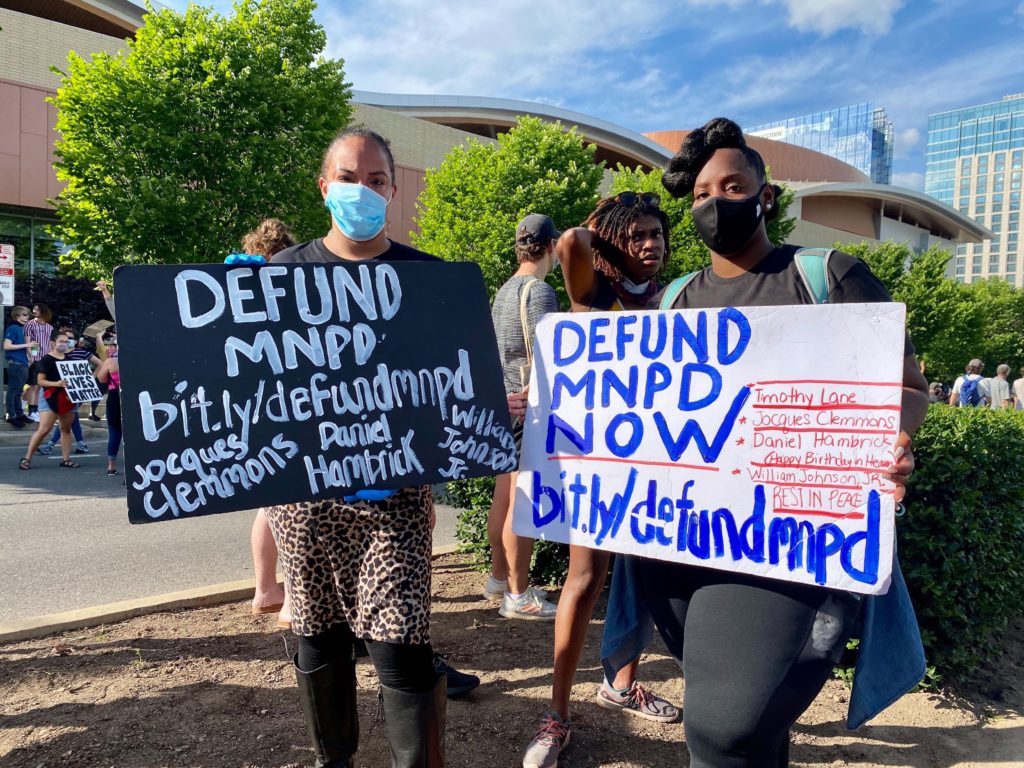

Local activists and lawmakers are trying to figure out what defunding the police could mean for Nashville. At a Black Lives Matter rally last weekend, the words “defund the police” echoed through the streets as protesters marched through downtown, some holding signs with the same phrase.

“I think they need to defund the police,” says demonstrator Ceejay Lynch. “They need to spend more on the needs of the community. Instead of policing communities, you need to build them up.”

Another protester, Jason Casale, says he wants the city shift funding from the Metro Nashville Police department to “schools, education, public healthcare — basically anything that’s for the population, instead of a group of people who have historically and systematically oppressed, particularly, people of color.”

For Casale, he says, “it should be disbanded entirely, and then an alternative system be in place.”

But the push to defund the MNPD has put some people on edge. The local Fraternal Order of Police recently tweeted that cutting the department’s budget would be a “pathway to anarchy and chaos.”

And Mayor John Cooper says MNPD should focus on reforms, like reviewing its use of force policies.

Cooper has signed onto former President Barack Obama’s Mayor’s Pledge to reevaluate its policies. The city also announced this week that it would formally ban chokeholds — which were already illegal under Tennessee law in most cases — and that the chief had sent a bulletin to officers reminding them to intervene if they see a colleague breaking the law or using excessive force.

But Lane says activists have asked for changes for years and they’ve never gone far enough.

“There’s no way to reform us out of these problems,” Lane says. “We need to invest in our communities that have been historically defunded, historically neglected. And we want to invest in us, because we know that when communities are thriving and healthy, there’s less crime to begin with.”

So, what might a new public safety model look like in Nashville? Rasheedat Fetuga has been thinking about this question for years.

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN News“It’s not about one person. It’s not about individual police officers,” Gideon’s Army founder Rasheedat Fetuga says at a press conference about defunding the police on June 13. “These are systemic issues that have to be changed, which is why we call for funding of restorative justice programs.”

“If Nashville is really serious about changing the culture of our city, if they’re really serious about the importance of defending black lives in the city, then they would pull money from spaces that aren’t working and put it into research-based models that are already proven to work, with the least amount of unintended consequences,” she says.

Fetuga is the founder of Gideon’s Army, a grassroots organization that works to build trust in communities that have rocky relationships with police by dealing with trauma head-on.

They mentor teens one-on-one. A team of Violence Interrupters responds during moments of crisis to prevent shootings. And when a crime does occur, the group brings together victims and perpetrators to talk through the harm that was caused and help them make amends.

Fetuga says the nonprofit has gotten a lot of verbal support from city leaders, but that raising money to expand its programming is a constant struggle.

“Every year, city council says, ‘Oh, we really value Gideon’s Army, but we don’t have the money,’ while they continue to push money into the Metro Police Department,” she says. “And it doesn’t make sense, when we know that, ultimately, policing doesn’t heal communities and it doesn’t build equity.”

Fetuga says she doesn’t want to completely replace the police department. But she would like to see restorative justice centers rather than police precincts, Violence Interrupters instead of officers in public housing, and a new emergency line equipped with mental health professionals, rather than police officers.

“I also think that money, when we defund, should be reallocated and put at the front end of issues,” she says, “for focusing more on prevention than we are on — it’s not even intervention. It’s reaction.”

Some Nashville council members do want to see significant cuts. One suggested slashing as much as $108 million from the department’s budget.

But the mayor’s budget proposes increasing spending on law enforcement, to add more officers to the force.

About police, I proposed keeping MNPD budget flat over FY20. Mayor proposes $2.6 million increase (up to $209 million). 5 CMs offer amendments:

Johnston & Vercher: add $2.6M to match Mayor's budget

Parker: down $2M

O'Connell: down $7M

Welsch: down $108M— Bob Mendes (@mendesbob) June 13, 2020

“This has been a really challenging environment to talk about how we are going to invest in our priorities,” says council member Freddie O’Connell, who suggested a $7 million cut.

But O’Connell says any drastic changes will probably have to wait. Between the tornadoes, a global pandemic and other budget woes, lawmakers haven’t had the time or energy to totally reimagine law enforcement, he says.

O’Connell hopes residents will have the opportunity to play a larger role in the next budget cycle. He suggests a year-long series of roundtables. And he hopes those who raised their voices in favor of defunding the police will continue to push for change.

“It’s going to be very interesting to see how many young people stay engaged in this conversation for a full year,” O’Connell says. “Or are they going to feel like, ‘Yes, we had this massive, amazing success at organizing that lasted for a couple weeks, a budget passed, and suddenly now everybody’s disillusioned and hates politics and politicians, because they didn’t get even close to what they asked for.”

Samantha Max is a Report for America corps member. Ambriehl Crutchfield contributed to this report.