Flooding risks are based on probability, but the standard equations may be outdated — or at least misunderstood.

In Nashville, the probability for “100-year” storms, or storms with a 1% chance of happening in a given year, are four times higher than federal projections, according to a new study by First Street Foundation.

The study, published in the Journal of Hydrology, found that about one-fifth of the nation faces such heightened risks for extreme rainfall.

“The analysis reveals that a significant number of highly populated areas are experiencing higher flood risk than what the local communities currently consider a 1-in-100-year event,” the authors wrote.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration calculates precipitation risks for communities by estimating the expected intensity, duration and frequency of rainfall events. For Nashville, NOAA has estimated that 3.2 inches of rain could fall in one hour during a 100-year storm event. The new study revises that estimate to 3.7 inches, or a 15% increase per hour.

NOAA considers historical data from weather stations equally in its analysis. The problem is that old rainfall data is less relevant than more recent records affected by climate change, and, given that most stations have about 100 years of data, the median year for NOAA records is approximately 1970.

“The understanding of precipitation expectations today is about 50 years out of date because that analysis assumes that the statistical characteristics of rainfall events have not changed over time,” the study authors wrote.

The study indicates that NOAA is aware of the problem and will revise its methods to incorporate climate change into its next precipitation analysis, which influences where and how communities build homes and infrastructure. The agency is not expected to update its precipitation standards until 2027.

Extreme rainfall in Tennessee is revealing a hidden health threat — hazardous chemical facilities

Fossil fuel burning is the dominant cause of climate change

Extreme rainfalls have become more frequent, intense and longer in recent decades. Since 1970, the average hour with rainfall in Nashville has gotten 12.5% wetter.

Probabilities are shifting with climate change, but there is not a “new normal,” as many folks say, because the world is still burning fossil fuels, cutting down forests and producing food in planet-warming ways. Storm events in the past few years, or even in the past few days, have been shattering records, and additional warming will make some types of storms worse.

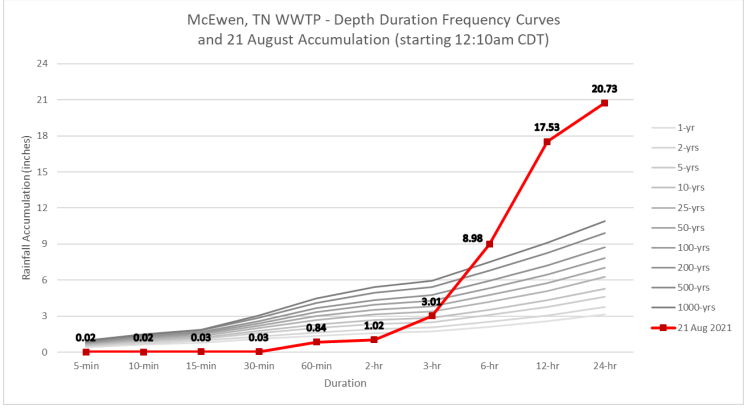

In 2021, nearly 21 inches of rain fell in the small town of McEwen and contributed to deadly flooding downstream in Waverly. This Tennessee storm set the national record for the heaviest 24-hour downpour in a non-coastal state. At its peak, the storm dropped 4.3 inches of rain in one hour. The highest rate was nearly 7 inches per hour.

Courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Courtesy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration The rainfall that caused catastrophic flooding in Waverly, Tennessee far exceeded what would be expected in a 1,000-year event.

A 1,000-year rainfall event is defined as a storm that has a 0.1% chance of happening in a given year. For a single day timeframe, the McEwen rain was nearly double what would be expected in a 1,000-year event.

On Wednesday, just north of Tennessee, a small town in Western Kentucky recorded more than 11 inches of rain. If verified, that will represent the new 24-hour rainfall record for the state of Kentucky. The rainfall was captured at a station that’s part of Kentucky’s statewide weather infrastructure, called a mesonet, which Tennessee does not have.

Climate change is intensifying the water cycle. Warmer air can hold more moisture, so clouds can bloat and dump more water during downpours — though there is a little more nuance to this science that may lead researchers to underestimate rain risks.

Future flooding patterns are even less certain, partially because flood severity varies greatly between different topographic features.

Urban development, especially in flood-prone areas, can also increase risks. As concrete covers more soil, absorption and runoff patterns change.

More: Dirt is key to understanding Tennessee’s environmental disasters in 2022. Let’s talk about it.

A single project might not have a big impact on flooding, but there is an accumulative, “thousand cuts” effect, said Ryan Jackwood, the science director at the Harpeth Conservancy.