On Dec. 2, 2020, after months of negotiations, Nashville’s Community Oversight Board and Metro Nashville Police signed a new memorandum of understanding, an agreement meant to guide their historically tense working relationship.

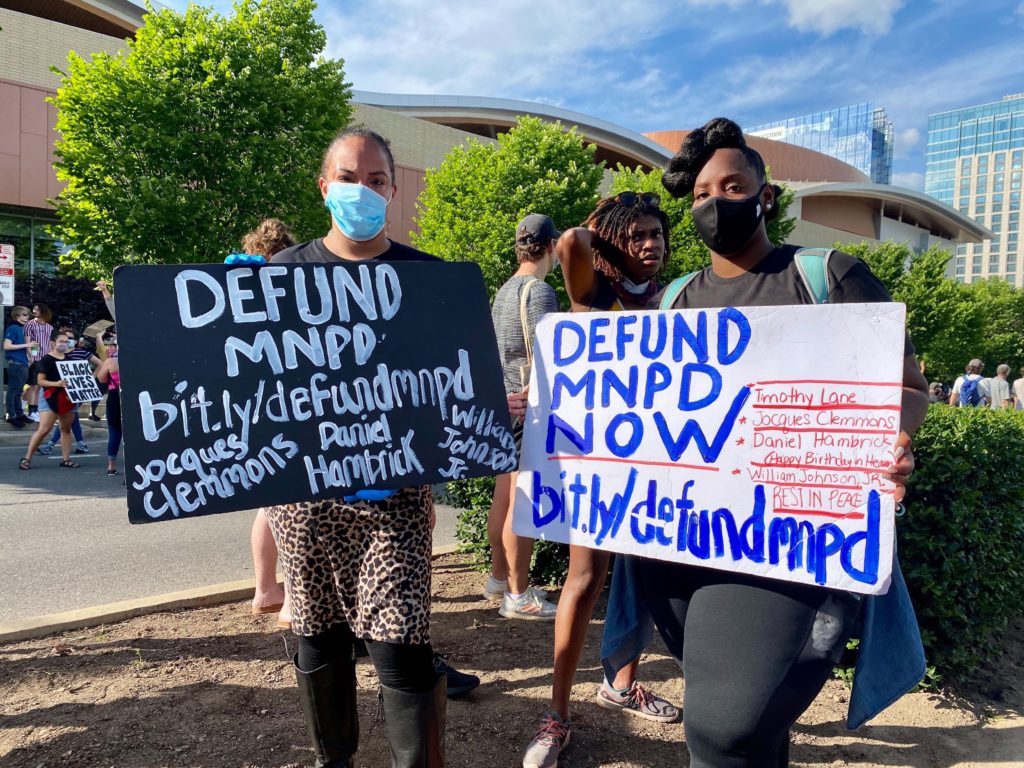

It was the year of the George Floyd protests, when people in all 50 states took to the streets to protest against police brutality and systemic racism. In downtown Nashville, the War Memorial Plaza became the center of the movement. Activists started calling it the Ida B. Wells Plaza — and later, the People’s Plaza. Newly-appointed Police Chief John Drake publicly voiced his support for the Community Oversight Board, and pledged to work with them — unlike his predecessor.

More: Reflecting on the People’s Plaza protests, three years later

It was a hopeful moment for police accountability.

Less than three years later, the Tennessee legislature passed a new law abolishing community oversight boards across the state. Now, a retired MNPD internal affairs lieutenant claims that top police officials worked to help get that law passed.

These allegations are the latest installment in the long, tense history of Nashvillians fighting for police oversight and MNPD resisting outside scrutiny.

Police killings have long been catalysts for calls for reform, including local efforts to found a community oversight board, as investigated by former WPLN criminal justice reporter Samantha Max in our podcast Deadly Force.

So let’s take a step back.

1973

Samantha Max WPLN News (File)

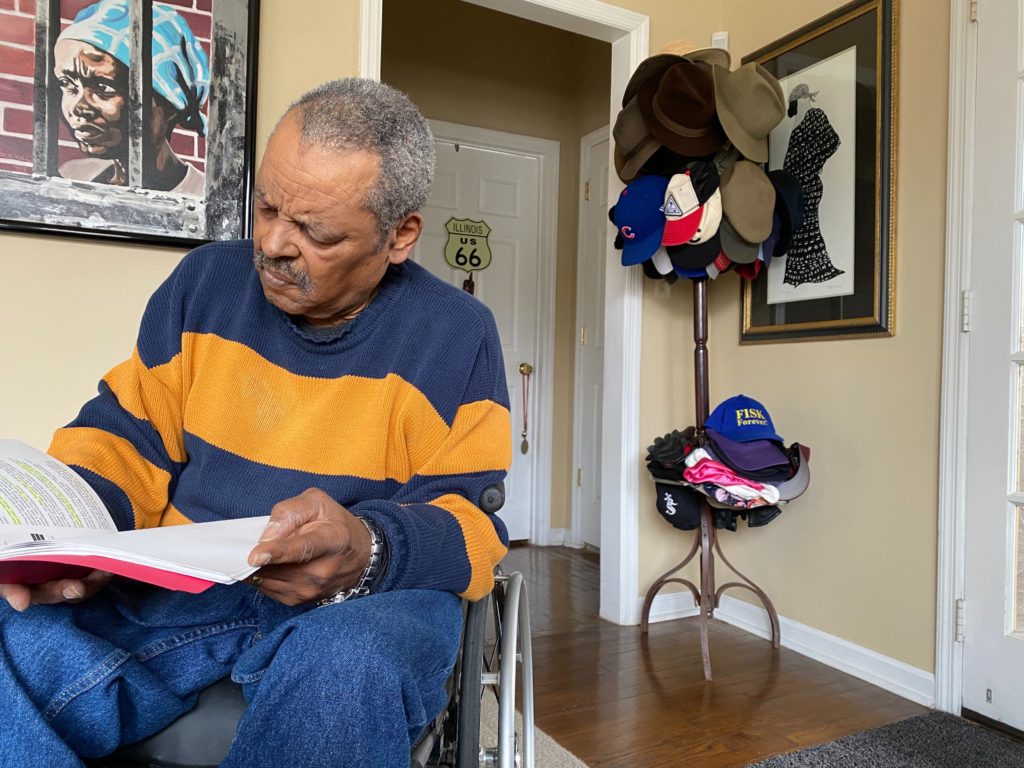

Samantha Max WPLN News (File)Longtime activist Walter Searcy moved to Nashville in 1967. He took part in rallies and marches in the aftermath of the police killings of Cedric Overton and Ronald Lee Joyce.

Two young, unarmed Black men — Cedric Overton and Ronald Lee Joyce — are shot and killed by MNPD in less than a year. Investigators later find that the officer who shot Overton planted a knife on his body.

The community is outraged. College students go on strike. About 30 local activist groups come together to form the Coalition Against Police Repression. One of the coalition’s key demands: a citizen committee to independently investigate allegations of police brutality and appoint a new police chief.

It’s the first, unsuccessful effort to create a community oversight board in Nashville. However, these kinds of boards were not a new concept at this point. The idea dates back to at least the 1920s and gained popularity during the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and ’60s.

1980s-90s

At least seven more people are shot and killed by police without any murder charges being filed. A disproportionate number of those killed are Black.

In 1996, Emmett Turner becomes Nashville’s first Black police chief.

In 1997, 23-year-old Leon Fisher is shot and killed by police after running from a traffic stop. The community is, once again, outraged. A Dollar General store is looted and set on fire. Turner tries to build bridges with the community, but defends the officer’s use of deadly force.

The idea of a community oversight board resurfaces in Nashville, but doesn’t go anywhere. Meanwhile, two other Tennessee cities establish civilian review boards: Memphis in 1994, and Knoxville in 1998.

2000s

In February, Turner sets up a new division to investigate complaints against MNPD employees, headed by a former Metro attorney — a civilian who has never served in law enforcement. This move is hugely unpopular within the department. The police union protests vigorously, and even tries to get the mayor to step in, but is unsuccessful.

A few weeks later, police shoot and kill three men in just one month: Timothy David Hayworth, Larry Davis and Chong Hwan An.

The shootings spark renewed calls for police reform. However, the department ultimately rules that all three shootings were justified, and the district attorney declines to press any charges.

Five years later, in 2005, MNPD begins keeping data on the use of deadly force. There is no way of knowing exactly how many people were killed by Nashville police before then.

2017

Tony Gonzalez WPLN

Tony Gonzalez WPLNA memorial to Jocques Clemmons was created in February after he was fatally shot by a Metro officer who will not face criminal charges.

In February, Jocques Clemmons, 31, is shot and killed by Metro Police officer Joshua Lippert after running away during a traffic stop.

Again, the community is outraged and calls for reform.

Activists from Community Oversight Now alongside the grassroots group Nashville Organized for Action and Hope, or NOAH, lead the renewed charge to establish a community oversight board.

A proposal is introduced in Metro Council, and is publicly opposed by MNPD and the Fraternal Order of Police.

2018

Chas Sisk WPLN

Chas Sisk WPLNSupporters of a Community Oversight Board gathered signatures during a rally in memory of Daniel Hambrick in Watkins Park .

After months of debate, Metro Council votes 25-5 against legislation to establish a COB.

Undeterred, Community Oversight Now and NOAH launch a successful campaign to get the proposal on that year’s ballot as an amendment to the city’s charter. In July, Daniel Hambrick, 25, is shot and killed by Metro Officer Andrew Delke. Video shows that Hambrick was running away when Delke shot him.

Listen: WPLN’s podcast ‘Deadly Force’

People take to the streets to protest, with some chanting: “We want a COB, not no PP (Policing Project)!”

That November, Nashvillians vote to establish a community oversight board in overwhelming numbers.

The measure wins by a 20% margin citywide with more than 134,000 votes and a majority in 29 of 35 Metro Council districts. On top of being popular, the new board is set to be more powerful than the existing review boards in Memphis and Knoxville.

2019

It’s a rocky year for the fledgling board.

Metro Council interviews over 150 nominees to serve on Nashville’s Community Oversight Board. They select nine, who serve alongside the two members appointed by the mayor’s office.

By February, Republican state legislators craft legislation to undo many of the board’s key provisions including:

- Their power to subpoena evidence

- Limitations on the involvement of former and current law enforcement officers

- Diversity requirements, which include socioeconomic status

Then-Mayor David Briley condemns the legislation, while Gov. Bill Lee publicly supports it. Ultimately, legislators land on a compromise: Nashville’s COB must send subpoena requests through Metro Council.

The board negotiates a seven-page memorandum with MNPD, outlining their powers and how their relationship will work.

Nevertheless, tensions quickly mount between the COB and MNPD. Chief Steve Anderson repeatedly declines to meet with the board. Police block COB investigators from crime scenes and refuse to share evidence.

Then, the COB’s first executive director resigns after less than a year on the job, citing stress and a lack of autonomy.

2020

Alexis Marshall WPLN News

Alexis Marshall WPLN NewsA crowd of thousands took a knee in remembrance of George Floyd on Lower Broadway during the March for Justice in summer 2020.

It’s a landmark year for police reform across the United States. On May 25, George Floyd is murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis, Minnesota. His death, along with the police killing of Breonna Taylor in Kentucky and the murder of Ahmaud Arbery in Georgia, sparks an international wave of protests against police brutality and systemic racism.

Nashville’s COB investigates several high-profile use of force incidents, and publishes recommendations for the department, including banning several types of neck restraints, requiring deescalation before officers use force and adding more specific wording in the department’s ban on shooting from a moving car.

That August, Chief Anderson abruptly resigns following a flurry of workplace harassment and discrimination controversies.

He is replaced by John Drake, who has been with the department for more than three decades. Chief Drake publicly pledges to work with the COB and to disband flex units, which had been criticized for making lots of traffic stops and stop-and-frisks.

2021

The Tennessee legislature passes a new law requiring members of a police oversight board to attend a citizens police academy within one year of joining. Otherwise, the entire board loses its authority.

The late state Rep. Bill Beck, D-Nashville, calls the law a “poison pill” for the community oversight process, and says there are already enough guidelines in place to ensure that board members are educated about law enforcement.

The Metro charter already required members of the Community Oversight Board to complete the Metro Nashville Police Department’s citizens academy, or an equivalent program. However, members used to be able to make up classes if they missed a session.

2023

The Republican supermajority in the Tennessee legislature passes a law dissolving community oversight boards, giving local governments a 120-day window to replace their COBs with less-powerful “review” boards.

Nashville’s Metro Council and COB scramble to reconstruct the board to be in compliance with the new law. In the end, the board shrinks from 11 to seven members, and loses most of its ability to conduct independent investigations.

2024

Metro Nashville Network

Metro Nashville Network Nashville Community Review Board member Alisha Haddock during an emergency meeting of the board.

On May 22, 2024, a retired Metro Nashville Police lieutenant files a 61-page complaint alleging that at least two high-ranking MNPD officials worked to overturn the city’s Community Oversight Board — and the department’s top leadership knew about it.

Garet Davidson, who served as the lieutenant of the Office of Professional Accountability from 2021 to 2024, claims that a deputy chief was given a “small, laser-engraved crystal-style award” for his work on advancing the law that banned community oversight boards in Tennessee. He also says that the department’s top leadership, including Chief Drake, were aware of these efforts.

The complaint has derailed negotiations for a memorandum of understanding between Nashville’s new Community Review Board and MNPD.

“We were ready to send over our first draft (of the MOA), and then, some of the people who would have been sitting in the room with us have been named in the complaint,” said board member Alisha Haddock. “So that is very problematic for us.”

Metro’s legal department has brought in independent, outside counsel to investigate Davidson’s full complaint. In the meantime, the future of the Community Review Board’s relationship with the police department it is designed to review remains uncertain.