Hospital capacity shortages have largely stayed out of sight during the pandemic. But a new study from Vanderbilt University Medical Center that followed patients in dire need of high-level life support finds that the shortages resulted in unnecessary deaths.

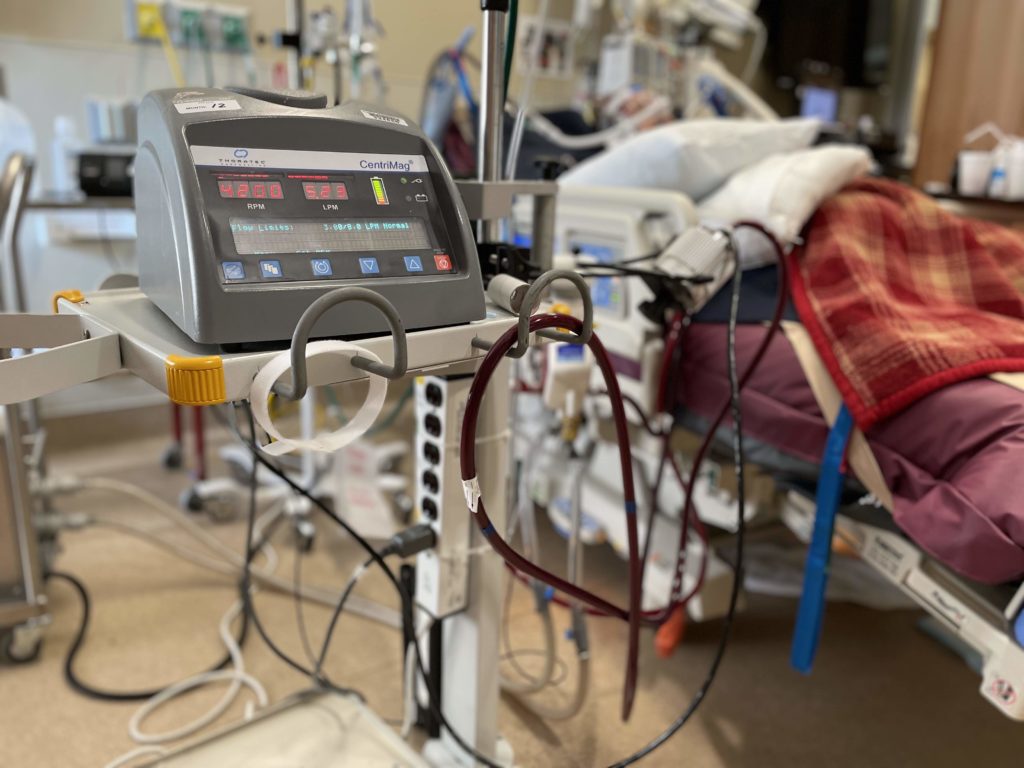

For critical COVID patients, ECMO is a risky, last-ditch effort to save their lives. Their blood is piped out of their body and a machine does the work of the heart and lungs. Usually, ECMO is only considered once a ventilator is no longer keeping their blood oxygen level high enough for survival.

During the Delta variant surge late last summer, ECMO was in short supply across the South. Vanderbilt’s unit was taking 10 to 15 calls a day from hospitals without ECMO looking for an open bed. Even patient families were making calls on the behalf of dying loved ones.

“‘There’s no beds. There’s no nurses. There’s no machines. There’s just not enough. We just physically can’t,'” nurse practitioner Whitney Gannon says she would tell people calling from hospitals around the South. “It’s the worst feeling in the world.”

But Gannon grew curious about what happened to the patients she had to turn down — especially those who were young and healthy enough to be good ECMO candidates with a higher likelihood of survival. She started checking back, informally. Many of them had died, including a pregnant woman.

So within a matter of weeks, she helped launch an official study. And Gannon’s team started taking every call, even when no beds were available.

“We wanted to know: Is this patient truly medically eligible for ECMO? Would we provide ECMO? And if we didn’t, we wanted to know what happened to that patient,” Gannon says.

Anne Rayner Courtesy VUMC

Anne Rayner Courtesy VUMCAn ECMO machine takes over for the heart and lungs when one or both fail. Vanderbilt University Medical Center only launched its ECMO center a year before the pandemic. And usually it had one or two patients. Even now, the max capacity is seven, largely because each patient requires so much staffing.

The results, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, are grim. Nearly 90% who couldn’t find a spot at an ECMO center died. And these were the patients who were young and previously healthy, with a median age of 40.

James Perkinson of Greenbriar is one of the lucky ones who found a bed. The 28-year-old machinist was taken off ECMO in late February after more than six weeks.

“It’s a miracle that I’m even able to have this second chance because of the ECMO,” he says from his hospital bed where he’s still recovering.

Being sedated for so long, Perkinson says he will have to relearn how to walk and use his arms, which could take more than a year to fully recover. But he’s alive for his wife and two young children.

The effectiveness of ECMO, which stands for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, has been questioned throughout the pandemic, even as use of the therapy spiked. Many centers slowed down after a study was published in The Lancet in late September, finding that the number of COVID patients dying on ECMO had worsened 15% since the beginning of the pandemic.

Even early on, roughly half weren’t surviving. And as the pandemic dragged on, more hospitals with less experience were using ECMO, and some expanded criteria to include older patients or those with risk factors like obesity who’ve been thought not to do as well. But there has been limited data.

Hospital capacity crunches have been central to the debate because ECMO requires even more staffing than patients on ventilators. And sometimes the patients stay on the therapy for months, not just weeks. Those patients need a one-on-one nurse around the clock because of the risk of blood clots or if one of the tubes pulled from the patient’s body.

One patient currently at Vanderbilt, which has just seven ECMO beds, has been there since the Delta surge last year, says Dr. Jonathan Casey.

“So you can imagine how it doesn’t take much to fill this resource even during a small wave,” he says.

Even during the ongoing Omicron surge, Casey says Vanderbilt has had times where transfer requests for ECMO were turned down. In Middle Tennessee, only the three largest medical centers — Centennial, Ascension Saint Thomas West and Vanderbilt — offer ECMO currently.

While the odds of survival with critical COVID patients are still roughly 50-50, the Vanderbilt study shows what happens if the therapy is unavailable.

“I’m trying to convince people that this is a resource worth investing in and then hoping people invest in those resources over time,” says Casey, who helped author the study.

Until there is broader access to ECMO, Casey says the country also needs to find a better way to decide who is prioritized for treatment, similar to how organ transplant allocation works. There is a national ECMO organization called the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization, but it doesn’t get involved with triaging patients yet.

The Vanderbilt researchers also conclude that it’s important to stick with patient criteria and limit ECMO primarily to those most likely to survive. A COVID patient who is more likely to spend months on ECMO only to die means several other patients may not get the opportunity.

“I still stand by this,” Gannon says. “I think patient selection is the most important component of ECMO care across the board.”

There are no firm guidelines for who should receive ECMO, which means each patient requires an individual judgement. So Gannon says she has compassion for those families who have called, desperate to find an open bed to give their loved one a last shot.

“I feel for those families completely,” she says. “I think they should keep fighting and shouting. And I can tell you if it were my family member, I would be the same way.”