A Nashville police officer shot and injured a 20-year-old last week at the scene of a car crash. The officer fired his weapon when a young man reached for a gun while taking his belongings out of the car.

It was the ninth shooting by local police this year. And it raises questions about how officers are trained to interact with people who have guns.

In January, it was Lamon Witherspoon. Nika Holbert in March, Jacob Griffin in May, Antonio King in August and Adrian Cameron in September. Last week, an officer shot and wounded Rod Reed.

2021 has far surpassed the typical number of annual shootings by Nashville police, which has fluctuated between zero and four since the department started tracking in 2005. In nearly every case this year, the person officers shot had a gun.

The spike in the use of deadly force comes at a time when gun ownership is surging.

“I think it’s a troubling, troubling situation for police officers,” says Daniel Nagin, a public policy professor at Carnegie Mellon University who researches the criminal justice system. Last year, he published a study that found states with a higher prevalence of guns had more deadly shootings by police.

“They’re frequently called upon to enter into dangerous situations,” Nagin says. “Somebody having a firearm or brandishing it is, I think, almost the definition of an example of a dangerous situation.”

In Tennessee, the chances of encountering someone with a firearm are high. Data from the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation show that gun purchases have risen dramatically in the past decade.

The agency processed the sale of about 400,000 firearms in 2011. Last year, that number had more than doubled to over 800,000. And that’s not even counting private sales without a background check.

Nagin says the ubiquity of guns can put both police and the public at risk.

“Police officers have the authority to use lethal force when they deem — they perceive — that they or bystanders are threatened,” he says.

Self-defense law typically protects police who shoot someone when they fear the person could endanger them or people nearby. The presence of a weapon usually allows them deadly force.

The Metro Nashville Police Department’s use-of-force training teaches officers that guns pose a threat. They’re repeatedly told to be ready to fire — to protect themselves and others before someone else can pull the trigger.

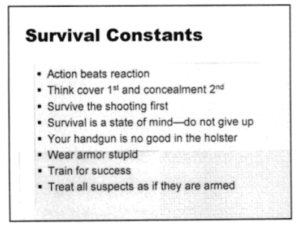

Courtesy Metro Nashville Police Department

Courtesy Metro Nashville Police Department A slide from a Metro Nashville Police Department officer survival course teaches recruits to “treat all suspects as if they are armed.”

“Realize every person is potentially dangerous,” reads a slide in an “Officer Survival” course presentation obtained by WPLN News. “Become aware that it may be necessary to take a life to save your own someone else’s,” it goes on.

The slide show also instructs recruits that “action beats reaction,” that “your handgun is no good in the holster” and to “treat all suspects as if they are armed.”

One slide tells recruits that the majority of shootings occur within the first 60 seconds of an encounter. And often, officers do shoot — sometimes within moments or even seconds after arriving on the scene.

Police Chief John Drake has declined multiple interview requests by WPLN News this year to discuss police shootings. After the latest shooting by one of his officers, Drake’s spokesperson said he had nothing to add while state agents investigate.

She noted the department has released body camera footage, which has become standard since the department began equipping its officer with cameras in the past couple years. However, the footage is often edited.

Samantha Max WPLN News

Samantha Max WPLN NewsMNPD Commander Scott Byrd took over the training division last fall, just before a surge in shootings by officers.

In an interview earlier this year, MNPD’s training commander, Scott Byrd, said he wasn’t sure why there have been so many shootings by police this year. But he speculated it could be connected to the rise in violent crime during the pandemic.

“Hard to say, but you can’t help but wonder if there isn’t a correlation there,” Byrd said.

He added that the department reviews each shooting and uses every case as an opportunity to consider changes to its curriculum.

But Rodney Reed, the father of the 20-year-old shot last week by Nashville police, says changes to the training need to come now. And he thinks the department should have updated its policies when a new Tennessee law took effect this summer that allows almost any adult to carry a gun without a permit.

“You got to be trained well enough to deal with people that have guns. Because you can’t say, ‘The minute you touch it, I’m going to shoot you,’ ” Reed says.

Reed’s son, Rod, was shot in the legs last week during a brief encounter with an officer at the scene of a car crash.

Rod Reed was getting his things out of the passenger side of a car that got smashed in the accident. The officer, Byron Boelter, told him to leave the stuff behind. When Reed reached for a gun on the dashboard, Boelter immediately fired.

Then, Reed was on the ground, screaming in pain. Boelter told him to put his hands up. He tried to assure Reed, said it would be OK. And he asked the 20-year-old why he had grabbed for the gun.

“I was just trying to get it out the car, sir,” Reed told him.

Rodney Reed and the rest of the family have multiple questions about how the officer acted. The body camera footage does not show that he ever identified himself as a police officer, and they’re not sure Rod could see his uniform when they talked through the window from opposite sides of the car.

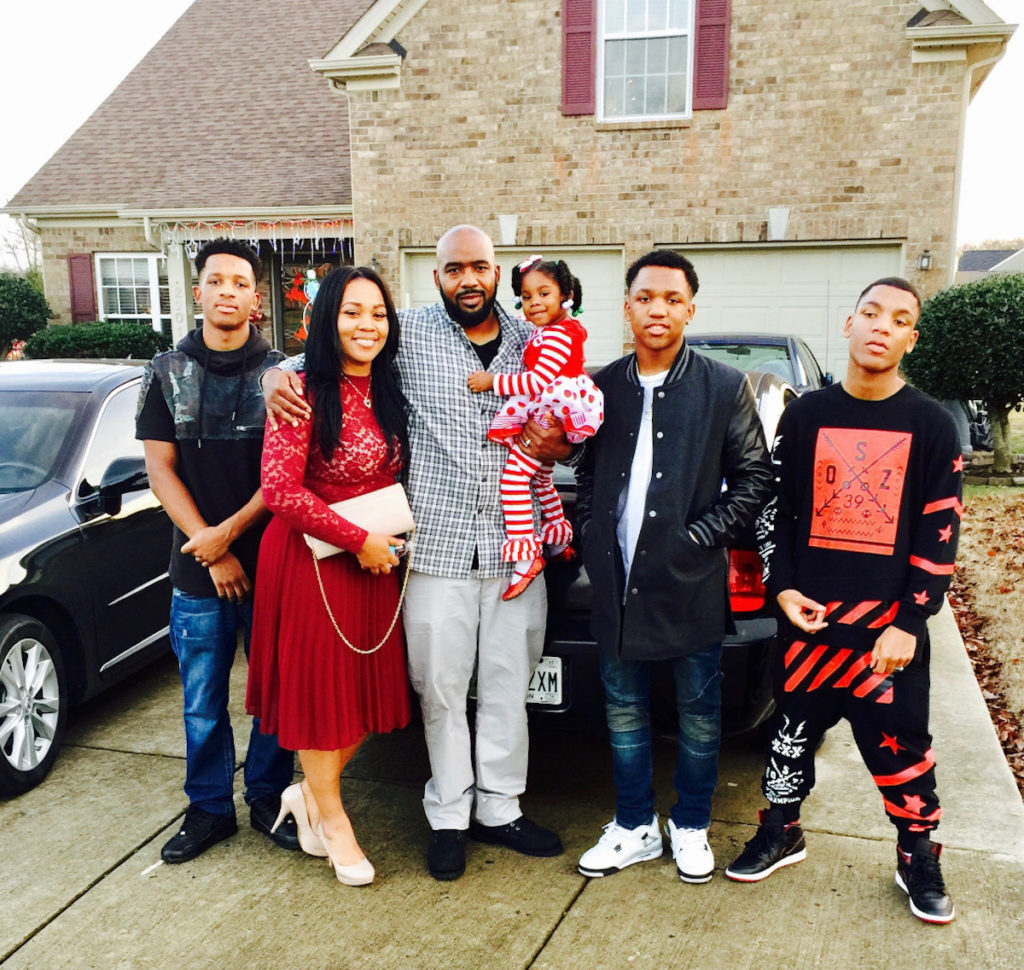

Rod Reed, center, with his family on signing day, when he committed to play football at Tennessee State University.

Plus, they note that in the video, Officer Boelter doesn’t give clear instructions not to touch the gun. Since Tennessee’s constitutional carry law has allowed so many more people to carry firearms, Reed thinks officers should be more prepared to deal with them in a calm way.

“You can’t come in saying, whoever got a gun, if they budge the wrong way, I’m going shoot them when you’re telling them they can have the gun,” he says.

Rod Reed was a year too young to be carrying a firearm — the age limit is 21, other than for members of the military — and he’s been booked in jail on a federal warrant for firearm and drug charges. The family says they had no knowledge of the warrant before the shooting and that Rod has been living at home while taking a gap year from Tennessee State University. Before the pandemic, he played defensive back on the football team.

Reed says he’s talked to his son about what to do if police pull him over — that there’s a chance he could get shot. But it’s a fear he hoped wouldn’t come true.

“You never in a million years think you’re going to see your child shot, and of course the video is just heart-wrenching,” Reed says. “But the good part of that is the blessing in that he’s alive.”