For most of the coronavirus pandemic, Nashville’s biggest hot spot for new cases has been in South Nashville — home to a large international community. But it’s taken city officials weeks to ramp up efforts that connect immigrants and refugees to the resources they need.

That has had Yam Kharel worried. He’s part of Nashville’s Bhutanese and Nepali community, and says they’ve seen more than 40 cases in a population of around 1,500.

“We first saw a few cases and then all of a sudden they started multiplying,” Kharel says. “We started seeing cases not in addition but in multiplication.”

He says there are a lot of reasons for that jump in cases, but one of them was access to accurate information. While coronavirus news has been nearly overwhelming in English, Kharel says fact-based, verified information translated in Nepali was sparse at the beginning of the outbreak.

Courtesy of Yam Kharel

Courtesy of Yam Kharel Volunteers from Nashville’s Nepali and Bhutanese community sort through food and supplies.

“It was not targeted to them,” Kharel says. “People thought that ‘That information is not for me. That’s for somebody that speaks English.’”

And to make the situation worse, Kharel says he’s seen misinformation spreading on social media — posts saying that people who eat certain foods or got specific vaccinations are immune to the virus.

That’s why Kharel started helping distribute social media videos, like a Q&A in Nepali. He’s been talking to Dinesh Chauwan, a Meharry Medical College resident, about the risk of the coronavirus.

Misinformation hasn’t just been a problem in the Bhutanese and Nepali community.

Ana Gutierrez, is a “community navigator” who’s been hired by Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition, or TIRRC. She says misinformation has also served as a major barrier to other immigrants, especially those who are undocumented.

“A lot of the times people believe that they will be asked about their immigration status,” she says, “or that if they don’t speak English whenever they go to these testing sites, then they won’t be treated because there’s not going to be anyone there to help them.”

Testing sites in Nashville are not asking for residents’ immigration status.

Coordinated Efforts To Help

Gutierrez says the people she’ll be helping as a navigator aren’t always aware of the resources they have access to.

“There are still communities that don’t have that trust yet, and it’s especially because they never were included in the process of making sure everyone was informed,” Gutierrez says.

There are now concerted efforts to change that. TIRRC’s new community navigator program is distributing information to immigrants and refugees, both about the virus and how to connect with food and financial assistance.

Meanwhile, Metro Public Health has hired six community health workers in partnership with TIRRC and the nonprofit Siloam Health. Amy Richardson is chief community health officer with Siloam, and she says workers are now calling daily to check in with immigrants and refugees who’ve tested positive for the virus to address their concerns.

“Maybe the person is worried about how they’re going to keep their kids educated while schools are not in session,” Richardson says, “or maybe the parent is worried about ‘How soon can I go back to work?’ or ‘Do I get sick leave?’”

Richardson says the coronavirus has amplified health disparities that predate the virus by a long shot. She hopes Metro’s community health workers can stay on after the virus passes, and that the relationships they’ve started to build outlast the pandemic.

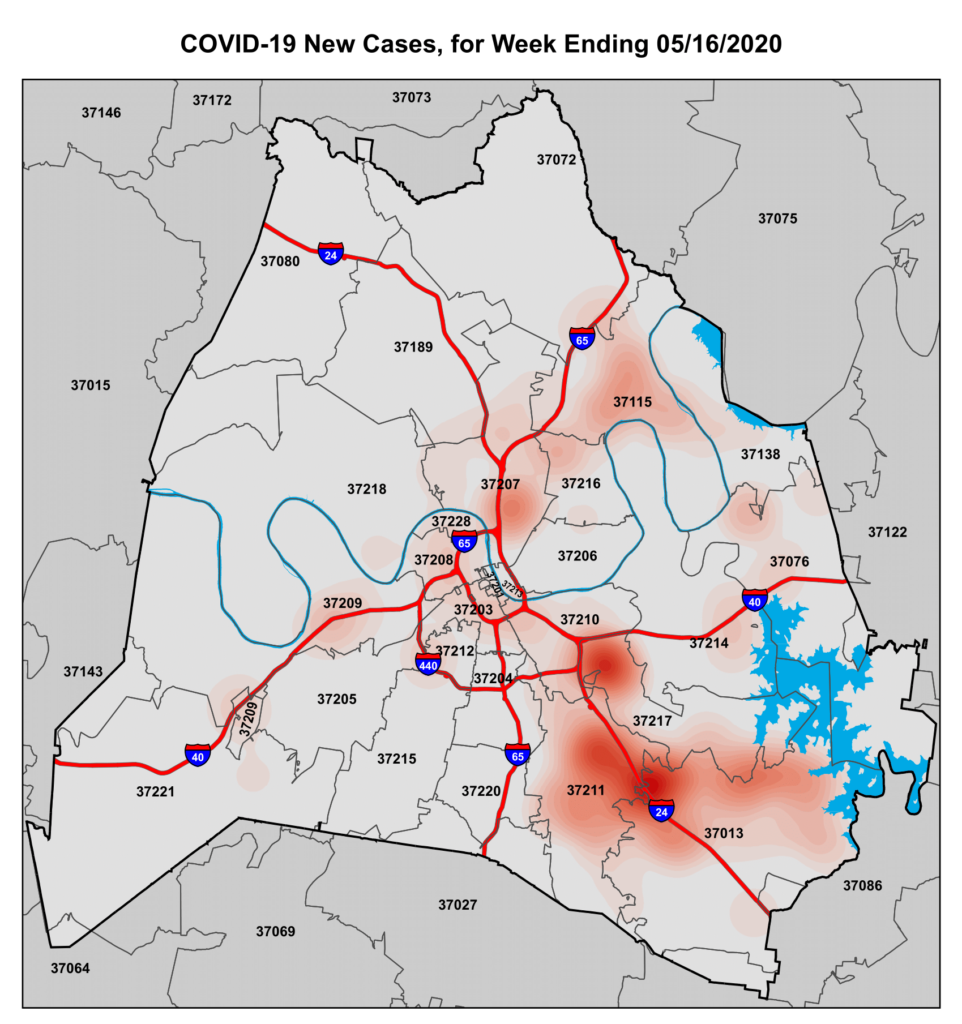

That partnership to dispatch community health workers became fully operational only within the last two weeks, according to Leslie Waller, who oversees the project for Metro Public Health. The first heat map showing South Nashville as a major hotspot was released six weeks ago. The most recent one shows the outbreak there is still the worst in Davidson County.

And public health officials were well aware that many immigrants are essential workers, who are especially vulnerable in an outbreak. Waller says Metro’s health department tried to make information available in different languages from the beginning but admits it wasn’t necessarily reaching its audience.

Finding People And Money

“We know that … on our social media platforms [and] with the Metro News station, a lot of our communities aren’t being reached through those ways,” Waller says, “so we knew we had to do something different, and that’s what we’re doing now.”

Waller says there are two big factors behind why it took weeks to mobilize community health workers. The first was putting together a qualified team.

“We simply didn’t have the staff to do as intensive of a response as we needed,” she says.

The second is a familiar one amid current budget struggles: funding. Waller says that despite calls for planning and preparation, policymakers often aren’t mobilized until they’re faced with an issue head-on.

“Unfortunately it does take something like a big number of cases of an infectious disease to get people’s attention to do something about it,” she says.

Now that Metro Health’s partnership is up and running, it’s a step toward developing bonds between immigrants and the public health agency, something Waller acknowledges is difficult.

“Whether we’re doing outreach to the immigrant or refugee communities that call Nashville home or other groups like our homeless population communication is always so key. It’s hard to incorporate trust,” she says, “especially when you’re working with or working for a government agency that a lot of people don’t tend to have much trust for.”