This time, it didn’t take much convincing for Mary Murphy to embrace home hospice. She had seen the help it could be when her mother died of Alzheimer’s disease in 2020, and so when her husband, Willie, neared the end of his life she embraced hospice again.

The Murphys’ house in a leafy Antioch neighborhood is their happy place — full of their treasures.

“He’s good to me — buys me anything I want,” she says, as she pulls a milky glass vase out of a floor-to-ceiling cabinet with mirrored shelves.

Willie bought Mary the display case to help her to show off all the trinkets she picks up at estate sales.

Down the hall, Willie lies in their bed, now unable to speak. His heart is giving out.

“You gonna wake up for a minute?” she asks as she cradles his head. She pats his back while he clears his throat. “Cough it out.”

Mary has been the primary caregiver for her husband with the help of a new hospice agency in Nashville focused on increasing use for comfort care at the end of life by Black families. Heart and Soul Hospice is owned and operated by people who share the same cultural background as the patients they’re trying to serve.

In their application to obtain a Certificate of Need in Tennessee, they make clear that they are Black and they intend to serve everyone but focus on African Americans who are currently underserved. Tennessee data show that in Nashville, just 19% of the hospice patients are Black though they make up 27% of the population.

Regulators granted the permission, despite the area not needing another hospice agency, based primarily on educating an underserved group.

In Mary Murphy’s first experience with hospice, her mother had suffered from dementia for decades, yet when transitioning to hospice came up with her mother, Murphy had many more concerns. She felt like she was giving up on her mom.

“My first thought was death,” she says.

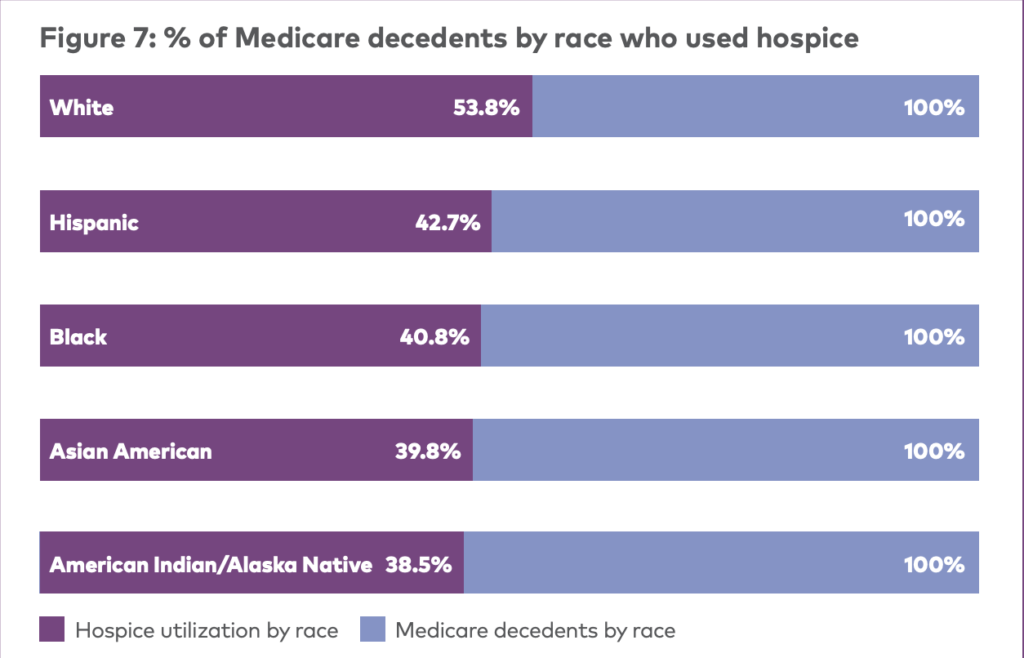

National data shows Black Medicare patients and their families are not making the move to comfort care as often as white patients. In 2019, roughly 41% died with the help of hospice, compared to white patients for whom the figure is 54% and climbing each year, according to data compiled annually by the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization.

Courtesy NHCPO

Courtesy NHCPO Source: National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization 2021 Facts and Figures with data from 2021 MedPAC report to Congress

Murphy’s mother survived nearly three years on hospice. The benefit is meant for those in the last six months of life, but predicting when the end will come is difficult, especially with dementia.

Murphy did most of the caregiving — which can be overwhelming — but hospice helped with a few baths a week, medication in the mail and any medical equipment they needed.

And most important to Murphy was the emotional support, which came mostly from her hospice nurse.

“Wasn’t no doctor going to come here, hold my hand, stay here until the funeral home came for her,” she says about the day her mother died.

This year, on the day after Thanksgiving, Willie Murphy died. And the same hospice nurse was at the Murphy home within minutes. She’d already stopped by that morning to check on him and returned as soon as Mary called and told her he wasn’t breathing.

“If you don’t feel like, ‘Oh my God, thank God I have hospice,’ if you can’t say that, then we’re doing something wrong,” says Keisha Mason, who is Heart and Soul’s director of nursing.

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsKeisha Mason is the nursing director for Heart and Soul Hospice and says she finds the perceived cost is often a barrier for Black families. It’s just hard for them to believe the in-home help is free to patients on Medicare and most private health insurance.

Mason is Black, like Murphy, and says in her view, there’s nothing fundamental keeping Black patients from using hospice except learning what the service can offer and that it’s basically free to patients — paid for by Medicare, Medicaid and most private health plans.

“I say to them, ‘If you see a bill, then call us, because you should not,’” she says.

As Mason has helped launch this new hospice agency, she’s begun using new language, calling hospice more than a Medicare benefit. She describes it as an entitlement.

“Just as you are entitled to unemployment, as you are entitled to Social Security, you are entitled to a hospice benefit,” she says.

The investors in Heart and Soul include David Turner of Detroit, Nashville pastor Rev. Sandy McClain and Andre Lee, who is the former hospital administrator on the campus of Nashville’s Meharry Medical College, a historically Black institution.

Lee and Turner also started a Black-focused hospice agency in Michigan, with plans to replicate the model in other states.

Lee says more families need to consider the alternative. Nursing homes are pricey. And even with Medicare, a hospital bill could be hefty.

“You’ll go in there and they’ll eat you alive,” he says. “I hate to say that bad about hospitals, but it’s true.”

Hospice research hasn’t come up with clear reasons why there’s a gap between white and Black families’ use of the benefit. Some speculate it’s related to spiritual beliefs and widespread mistrust in the medical system due to decades of discrimination.

The hospice industry’s national trade group, the NHCPO, released a “toolkit” this year. It recommends connecting with influential DJs and partnering with Black pastors. But also just hiring more Black nurses.

Lee says it’s not overly complicated.

“A lot of hospices don’t employ enough Black people,” he says. “We all feel comfortable when you see someone over there that looks like you.”

Well established hospice agencies have been attempting to minimize any barriers with their own diversity initiatives. Michelle Drayton of Visiting Nurse Service of New York says her large agency has been meeting with ministers who counsel families dealing with failing health.

“Many of them did not fully understand what hospice was,” she says. “They had many of the same sort of misperceptions.”

Whether it’s an upstart hospice company or one of the oldest in the country, everyone still has a lot of end-of-life educating to do to bridge the racial gap, Drayton says. “We’re not just handing out a brochure.”