Some of the closest witnesses to the Nashville civil rights movement were photographers from the city’s two major newspapers at the time, The Tennessean and the Nashville Banner. A selection of their photos — and the Frist Art Museum’s latest exhibit that displays them — offer a glimpse into how media outlets chose to cover the events.

After a bomb exploded at the home of prominent black attorney Alexander Looby in 1960, civil rights leaders organized a silent march from North Nashville to downtown — an event captured on camera by Tennessean photographer Jack Corn.

Corn recalls dashing ahead of the march to capture the iconic shot of Fisk student Diane Nash in the middle of the front row. He would cover various civil rights marches, protests and clashes for the next several years.

“I don’t sit back and let someone else do the big story of the day. That was the biggest story of the day, and I wanted to be there.”

Despite the drama of the photos, photographers didn’t relish the assignments, Corn remembers.

“I mean, you’re going somewhere and you know people are going to try to punch you out. It’s scary. If you were human, it wasn’t fun.”

But as scary as it was for the photographers, it was certainly more tumultuous for the protesters themselves. One photo from the Nashville Banner shows white men pulling a black student off a stool during a sit-in. Another, from The Tennessean, captures police dragging away a protester.

Curator Katie Delmez chose 50 pictures — from 1957, school desegregation in Nashville, to 1968, the wake of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. She says she wanted to include parts of history that show the negative aspects of Nashville at the time.

“I think Nashville thinks of itself as being a very progressive place where the civil rights movement was very civil here, and on the one hand it was, but there were some dark moments too,” she says.

Delmez also found it interesting how photographers from the two papers covered the events differently. The Tennessean was unabashedly liberal, led by outspoken civil rights supporter John Seigenthaler. Its journalists were more sympathetic to the movement.

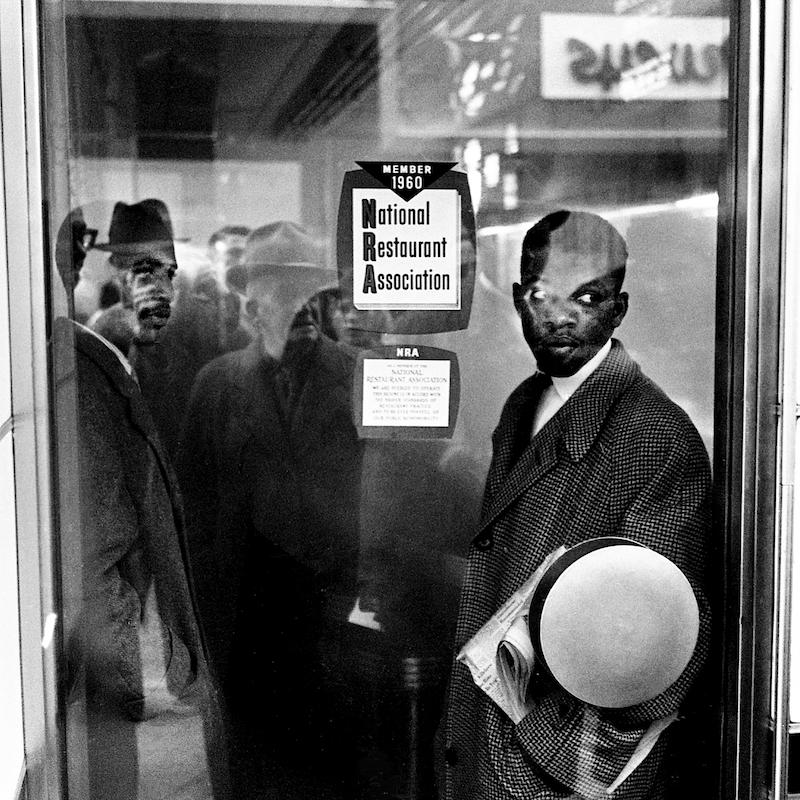

The now-defunct Nashville Banner tended to focus more on the violence of the events — if it covered them at all. Current Tennessean photographer Larry McCormack, who served as an adviser for the Frist exhibit, says many Banner photos, including many that are in the exhibit, were never actually published.

“A lot of these were turned over to the police so they could identify who was in the crowd,” he says. “This was Nashville in 1960-something.”

Looking back, it’s easy to see these photos as impartial historic snapshots. But at the time, the battles over desegregation and civil rights were so fierce that even a photograph could be used as a tool to sway public opinion.

The exhibit “We Shall Overcome” is on display in the Frist Art Museum’s free community arts gallery through mid-October.