In June, a tiny puncture in a 72-year-old pipeline leaked thousands of barrels worth of crude oil into Chester County.

The incident – Tennessee’s second-largest crude oil spill to date – impacted local water, soil and wildlife, according to a new report from the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, or PHMSA.

Courtesy Protect Our Aquifer

Courtesy Protect Our Aquifer The Mid-Valley Pipeline Company cuts through Tennesssee on its path from Texas to Michigan.

The breach was an uncommon error: a worker clearing vegetation in the transmission right-of-way for the Mid-Valley Pipeline Company, the name of the 1,000-mile interstate pipeline, hit the structure with a skid steer with a mower attachment, which is basically an industrial-strength lawn mower.

The steel pipeline was likely “exposed due to loss of cover,” the report said.

But the cleanup has been fairly successful, thanks to the local topography, weather and emergency response time, according to Steve Spurlin, EPA’s federal on-scene coordinator.

“The company responded well to the incident,” Spurlin said.

Multiple spills have happened on the Mid-Valley Pipeline, including Tennessee’s largest spill in Clarksville in 1988, over the decades. Its owner, Energy Transfer Partners, is better known for the Dakota Access Pipeline, a nearly 1,200-mile line that has been the subject of protests and ongoing lawsuits.

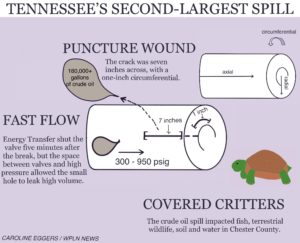

A seven-inch hole released 180,000+ gallons

The spill happened shortly after noon on June 29. The pipeline operator remotely closed the nearest valve five minutes after the breach, and emergency responders installed a mechanical clamp over the hole about 24 hours later to stop the leak.

But oil escaped quickly. The distance between the segment initially isolated by valves was about 300,000 feet, and the pipeline is highly pressurized, so a small nick released a deluge. PHMSA said the crack was just seven inches across and one inch down the curved structure.

Pipeline operators have increased pressurization in recent years because of the past decade’s fracking boom, and, in 2015, the U.S. lifted a 40-year-old oil export ban – so increasingly consolidated companies are literally pushing product faster than ever, Scott Banbury, of Tennessee’s Sierra Club, told This Is Nashville last month. He said these trends are especially concerning with the current lack of oversight.

“Most of these companies are self-reporting, self-regulating, and we only see the intervention of federal agencies, or state agencies, when there is a catastrophic accident,” Banbury said.

The Chester County spill size was re-estimated at 4,345 barrels, or roughly 182,000 gallons, and 3,300 barrels reached the nearby Horse Creek. About 75% of the total oil has been recovered, officially, but more oil has been captured in excavated soil, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, which helped organize the cleanup.

In the past month, workers have recovered oil from Horse Creek, excavated creekbank soils and re-injected recovered oil into the pipeline. Responders are still excavating soils near the pipeline discharge point, and there will be ongoing residual oil collection and water quality monitoring, according to EPA.

Terrain influences the success of oil spill cleanups, and Spurlin said Chester County’s flat landscape proved very manageable. Natural features like hills or swamp-like terrain, on the other hand, make it challenging for responders to get heavy equipment near spill sites or impacted waterways.

This cleanup involved excavating soil about six feet down and sucking up oil from the creek via a hose attached to a tank. The latter is less effective if not positioned adjacent to a waterway.

“It’s kind of like using a short straw versus a long straw,” Spurlin said. “The longer you make the straw, the harder it is to pull the oil or material through it.”

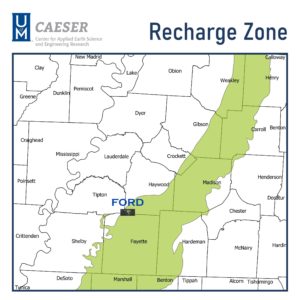

Courtesy University of Memphis

Courtesy University of Memphis The recharge zone for the Memphis Sand Aquifer dips into Chester County.

The Chester County site is located very close to the Memphis Sand Aquifer recharge zone, an area of porous earth that feeds directly into Tennessee’s largest groundwater source. Horse Creek flows into the South Forked River, which connects to the recharge zone, but responders were able to prevent oil from reaching the river.

“That would have made cleanup harder…potentially impacting drinking water on a much wider scale,” said Sarah Houston, director of the Memphis-based Protect Our Aquifer.

In the other direction, starting one county over, there is karst, which is fractured limestone terrain that readily connects water flowing underground.

Drought conditions made the spill easier to contain

Weather conditions also affected the cleanup. Chester County was in moderate to severe drought during the incident, so the water in Horse Creek was low and fairly stationary – it would have been a different story if a recent heavy rain fell right after the spill.

“That benefited them greatly here,” Spurlin said. “Because it’s a slow-moving stream, they brought in what are called drum skimmers … a rotating piece of equipment that sits on the surface of the creek, or the water, and spins. And as it spins, it picks up the oil and then it’s pumped to a holding tank.”

At this time, the bill for the spill is estimated at nearly $4.7 million, about $2.3 million for the emergency response effort and about $2.1 million for the environmental remediation.

The spill impacted fish, land animals, water and soil, according to the report, which does not include details about these impacts. EPA confirmed that turtles were among species impacted, but the final assessments for the numbers impacted have not yet been released.

Long-term remediation will be overseen by Energy Transfer and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. TDEC previously declined to comment on cleanup activities, but a spokesperson said the agency is conducting water monitoring.

The anticipated remediation actions are to recover surface water, groundwater and soil. There are no additional plans for vegetation or wildlife, according to PHMSA’s report.

Right-of-ways can often serve as prairie habitat for some plant and animal species. Following the spill, there were concerns about the whorled sunflower, an endangered plant that is dependent on prairie-like habitats and was first discovered in Chester County (the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service recently announced a recovery plan for it). There is a native population of the sunflower about 10 miles downstream of the incident site, on a different creek but within the same watershed. But EPA said the spill did not impact any sunflowers.