Developers may soon face fewer environmental regulations in Tennessee.

The state Senate passed a bill on Monday to remove some legal protections for wetlands, the saturated ecosystems that flow between waterways, land and animals. The bill could come before the full House for a vote within the next two weeks.

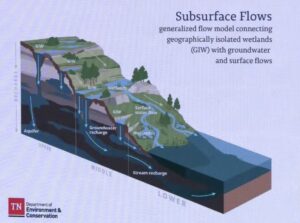

Wetlands are limited natural resources — especially isolated wetlands, a misnomer for wetlands that connect to bodies of water through groundwater or storm flows. The bill targets about half or more of Tennessee’s 320,000 acres of isolated wetlands. These wetlands are considered highly valuable for their ability to hold floodwaters, limit pollution from entering rivers and lakes, and provide habitat for copious plants and animals.

But the development industry has long sought to deregulate these natural features, which have disappeared from Tennessee maps primarily due to farms and concrete.

The U.S. lost federal protections on isolated wetlands two years ago

The Clean Water Act is the nation’s primary law for protecting water from pollution.

In 2023, the Supreme Court weakened this law after a narrow ruling in a case called Sackett v. EPA, threatening the majority of the nation’s previously protected wetlands. The case did not immediately affect Tennessee, which set up statewide protections prior to the federal law.

The plaintiffs in the case were represented by the Pacific Legal Foundation.

The Pacific Legal Foundation, which has received funding from fossil fuel billionaire Charles Koch, is a nonprofit law group known for fighting regulations to benefit special interests. The group argued that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration shouldn’t regulate tobacco. Tobacco giant Philip Morris once described the Pacific Legal Foundation as a “strategic key ally” and enlisted their help in attacking the Environmental Protection Agency over its finding that secondhand smoke is a carcinogen, prior to other regulation efforts. The group has also argued that EPA shouldn’t regulate greenhouse gas emissions, the pollution that causes climate change.

More recently, the Pacific Legal Foundation argued that EPA shouldn’t regulate isolated wetlands. The group has continued such efforts at the state level.

“When addressing environmental regulations, we’re dealing with property rights,” the Pacific Legal Foundation’s Kileen Lindgren said during a Tennessee state House hearing last month. Lindgren was one of three people to publicly speak in favor of legislation to deregulate Tennessee’s wetlands this year.

The sentiment was echoed by the other two lobbyists, who represented homebuilders and the Tennessee Chamber of Commerce and Industry, a group that has fought construction regulations before.

“This bill is ultimately about property rights for Tennesseans, and it raises the bar for the state to tell property owners what they can and can’t do with their property,” Mallorie Kerby, a lobbyist for Bass, Berry and Sims, said during a state Senate last month. She said she represented both the chamber and a group called Build Tennessee Housing.

The third person to speak in support, the chamber’s R.J. Gibson, read a nearly identical line a week later — an idea also championed by the bill sponsor.

“What this bill does is try to take the private property right, kind of take the thumb off and move it fractionally back in favor of the property owner,” said Rep. Kevin Vaughan, R-Collierville, the sponsor of the bill and a developer.

Under the bill, the non-government property owners, in virtually all cases, will be developers. The measure would allow these developers to build over small wetlands across Tennessee without having to pay for any environmental restoration to offset losses.

Right now, developers are also financially incentivized to avoid building on wetlands. That system will go away if the bill passes.

Widespread ecological and economic harm

The bill targets “geographically isolated wetlands.” These types of wetlands interact with the surrounding ecosystems by holding flood waters, filtering pollutants, providing habitat and recharging streams, rivers and aquifers. A recent study found that small, isolated wetlands are better at protecting downstream lakes or rivers from pollution than connected wetlands.

Wetland loss can, in turn, lead to increased flooding, worse water quality and loss of biodiversity.

Without protections, environmental experts warn that developers will potentially be able to cause significant harm — one little slice at a time.

“It’s kind of like death by a thousand cuts,” Sarah Houston, the director of Protect Our Aquifer, a water advocacy group in West Tennessee, said during a hearing last month.

Wetlands also have economic value. Tennessee researchers estimated that an acre of isolated wetland is worth $50,000 dollars. Wetlands in Midwestern states may save homeowners billions of dollars each year due to their natural flood defenses, according to a recent report by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

“The only people who we know will benefit from this are private developers, and that wealth will not trickle down to everyday Tennesseans,” Rep. Justin Jones, D-Nashville, said during a hearing.

Tennessee has been rapidly expanding: The state has consistently ranked among the top 10 for population expansion in recent years, with a net increase of about 315,000 residents between 2020 and 2024.

Advocates of the wetlands bill have argued that deregulating wetlands could lower housing costs for people, but there is no clear evidence to support that idea — even if developers may save money. A 2007 federal housing study during the George W. Bush administration concluded that wetland regulations contribute to about .08% of a total development project cost.

Wetland destruction can also affect the property value and safety of neighboring homes and communities because it can change how water flows across land. That is why Tennessee law has regulated their protection, according to George Nolan, the Tennessee director of the Southern Environmental Law Center.

“Not only does our legal system recognize property rights, but it recognizes the rights of neighbors,” Nolan said. “Just because someone owns property doesn’t mean they can do whatever they want regardless of the impact to neighbors.”

For example, if someone has a stream running through their property, they are not allowed to dam it up to keep the water for themselves because the stream is considered “waters of the state,” Nolan said. Wetlands are also, currently, considered waters of the state under Tennessee law.

Wetlands regulations are changing across the nation

After the 2023 Supreme Court ruling, as much as 84% of wetlands previously covered by federal law are no longer protected nationwide, representing about 70 million acres, according to a new report by the Natural Resources Defense Council. The Trump administration has suggested that it plans to exempt even more wetlands and streams.

Several states have established new wetland protections in anticipation or response to the Supreme Court decision, and two states have rolled back protections.

If Tennessee passes the bill in its current form, the state will lose regulations for about half or more of its isolated wetland acres and as much as 80% or more of its individual wetlands, based on the latest state survey.

In terms of the wetlands likely to be present in common development scenarios, the state will effectively lose most of its protections.