Kyle Kopec gets a kick out of leading tours of the run-down hospitals his company is snapping up, pointing out relics of poor management left by a revolving door of operators.

At a hospital in the town of Erin, Tennessee, about a 90-minute drive from Nashville, the X-ray machine is broken and can’t be repaired.

“This system is so old, it’s been using a floppy disk,” said Kopec, who just turned 23, marveling at the bendy black square that doesn’t have enough memory to hold a single photo. “I’ve never actually seen a floppy disk in use. I’ve seen them in the Smithsonian.”

West Tennessee has been ground zero for rural hospital closures since 2010. And several remain on the brink, including Houston County Community Hospital in Erin.

Much of the facility’s equipment is older than Kopec. And he said Medicare is penalizing the hospital with reduced payments for using outdated technology, he said.

The attic houses a ham radio system that never got much use. On the roof, Kopec pries open a panel on the giant HVAC unit, which is currently the only place the thermostat can be adjusted. And inside, he sweeps through a recently renovated emergency room that’s never been used. Its doors are too narrow for a gurney, among other problems that need fixing.

“If you’d like, we can try and wheel that bed through and see what happens,” Kopec said, wryly.

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsKyle Kopec of Braden Health opens the panel on the roof of Houston County Community Hospital, which is the only place to adjust the thermostat at the moment.

An old operating room is temporarily housing the ER while Kopec’s company, Braden Health, works on renovations.

Kopec’s official title is chief compliance officer; he’s really second-in-command. He crisscrosses Tennessee and other Southern states in a private plane (that he pilots), negotiating deals to take over distressed or closed hospitals.

Braden Health, based in Southwest Florida, has four hospitals in West Tennessee at varying stages in the acquisition process. Its first, in Lexington, Tennessee, has remained open since it was purchased in 2020. The facility was offloaded by Quorum Health, based in Brentwood, Tennessee, and just days from closing. Quorum has since declared bankruptcy.

On the ground in Braden’s hospitals, Kopec bounces through halls, greeting nurses and clerical staff by name with a confidence that belies his age and experience. He’s a year out of college — a 2019 intern in the Trump White House (though the post, he points out, was not political and part of his role in the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary).

Kopec uses a cockpit analogy to explain how Braden Health can use its know-how to help small hospitals no one has been able to stabilize: In a mid-flight emergency, someone who’s not a pilot first might think to put down the landing gear. A pilot, he said, would know that at 300 mph, the landing gear would get sheared off.

Similarly, rural hospitals require specialized knowledge. And the stakes are life and death.

“They’re not the most complicated things in the world,” Kopec said. “But if you don’t know exactly how to run them you’re just going to run them straight into the ground. Or worse you’re going to crash into a bunch of people.”

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsHouston County Community Hospital was purchased by the local government in 2013 for $2.4 million in order to avoid closure. Now the county, under the leadership of Mayor James Bridges, has struck a deal to sell it for just $1 to Braden Health, who pledges to make needed investments in the facility and run it as a hospital.

To prevent the hospital’s closure in 2013, Houston County had bought the local community hospital for $2.4 million. Like those inexperienced airplane pilots Kopec described, Mayor James Bridges said no one knew what they were doing.

“We had no business being in the hospital business,” Bridges said. “The majority of county governments do not have the expertise and the education and knowledge that it takes to run health care facilities in 2022.”

Those with the most experience, like big corporate hospital chains based nearby in Nashville, have been getting out of the small hospital business too. So communities have seen unqualified managers come and go. Some even got in trouble for shady billing practices.

In nearby Decatur County, where Braden Health is also taking over the local hospital, the previous operator has been indicted on theft charges. And the problems were so bad that the Tennessee comptroller determined the hospital was endangering the finances of the entire county.

“You’re looking to someone who supposedly knows what to do, who can supposedly solve the issue. And you trust them, then you’re disappointed,” said Lori Brasher, who sits on Decatur County’s economic development board. “And not disappointed once but disappointed multiple times.”

Brasher said she has much more confidence in Braden Health, which she said has concrete reopening plans, though they’ve been delayed by unresolved insurance issues. But local residents still have trouble stomaching the sticker price. There are many pages to the deal including tax breaks and required investments, but the bottom line is Decatur County agreed to sell its hospital for $100.

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsLori Brasher, an accountant who sits on the Decatur County Industrial Development Board, says her community has been burned by multiple companies who said they could run the local hospital. Now they’ve struck a deal to hand over the facility to Braden Health.

The deal for Houston County was just $1, even though the property appraisal exceeds $3 million. And an agreement to take over Haywood County’s shuttered hospital was a similarly symbolic payment.

But the agreements require Braden Health to invest millions in each site, in both new medical technology and rehabbing the buildings, or else the hospital reverts to the counties. Some are in rough shape and have to be reopened.

On a tour of Decatur County General, abandoned by the former owner two years ago, Kopec unlocks a walk-in freezer that reeks of rotting meat.

“If you look at the bottom, those are a bunch of dead maggots that didn’t make it out,” he said.

The smell of mold fills the halls. Pipes froze and burst while the hospital sat vacant. It took days for local emergency responders to see water spilling out of the building.

The Decatur County General deal requires Braden to invest at least $2 million into the facility. Most of the funding for restoring these facilities comes from Dr. Beau Braden, who founded Braden Health.

“I understand the perspective that a lot of people would have, that thinks that it’s worth a lot more,” Braden said of the hospitals his company is taking over. “But if you look honestly at a lot of transactions that take place with rural hospitals and how many liabilities are tied up with them, there’s really not a lot of value there.”

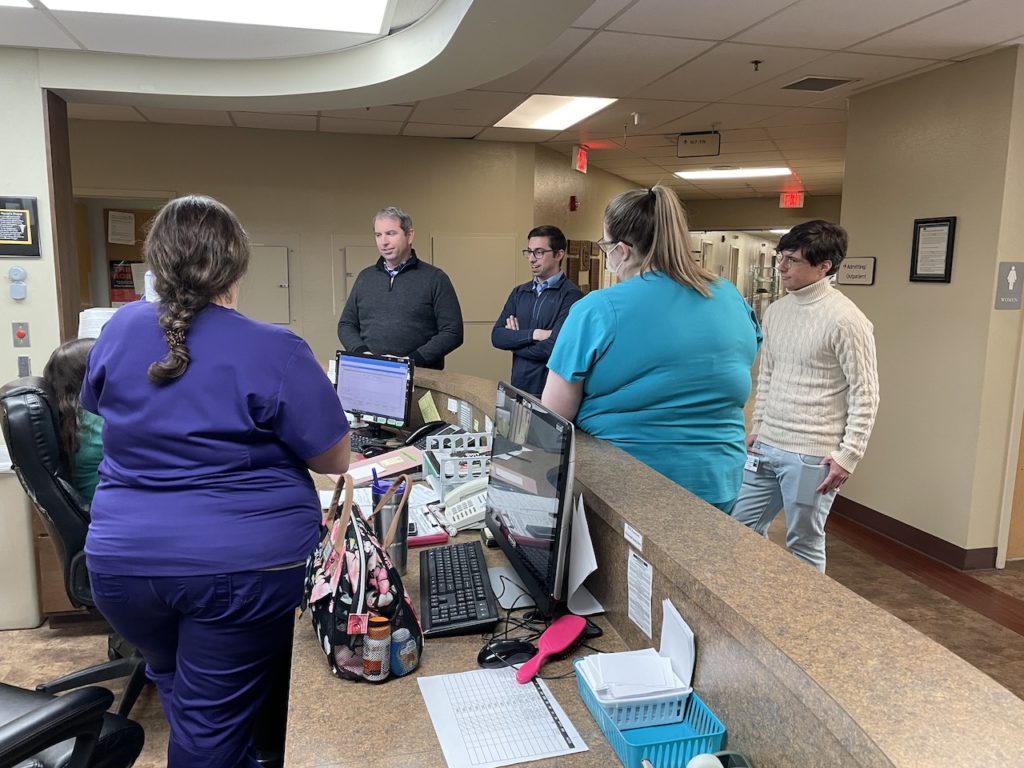

Blake Farmer WPLN News (file)

Blake Farmer WPLN News (file)Dr. Beau Braden (center), founder of Braden Health, speaks to employees gathered at the nurse station in Houston County Community Hospital. Braden is finalizing the acquisition but already helping run the facility.

Braden is an emergency physician who got into the hospital-buying business after trying to build a new hospital in Southwest Florida, where he owns a large rural clinic. After running into regulatory roadblocks, he saw more opportunity reopening hospitals — which brought him to Tennessee. The state has experienced 16 closures since 2010 — second only to the far more populous state of Texas, which has had 21 closures in the same period.

In West Tennessee, Braden aims to build a mini network that could share staff and supplies as needed. He said there’s no secret sauce, in his mind, except that small hospitals require just as much attention as big medical centers — especially since their profit margins are so thin. Braden focuses on improving technology in ways that health insurers reward, managing nurse staffing so there aren’t too many people working when patient volumes are low and watching medical supply inventories like a hawk to cut waste.

“A lot of people aren’t willing to put in the time, effort, energy and work for a small hospital with less than 25 beds. But it needs just as much time, energy and effort as a hospital with 300 beds,” Braden said. “I just see there’s a huge need in rural hospitals and not a lot of people who can focus their time doing it.”

Braden said he can understand any skepticism, even from the employees. They’ve heard turnaround promises before and even they can be wary of the care they’d get at such a run-down facility.

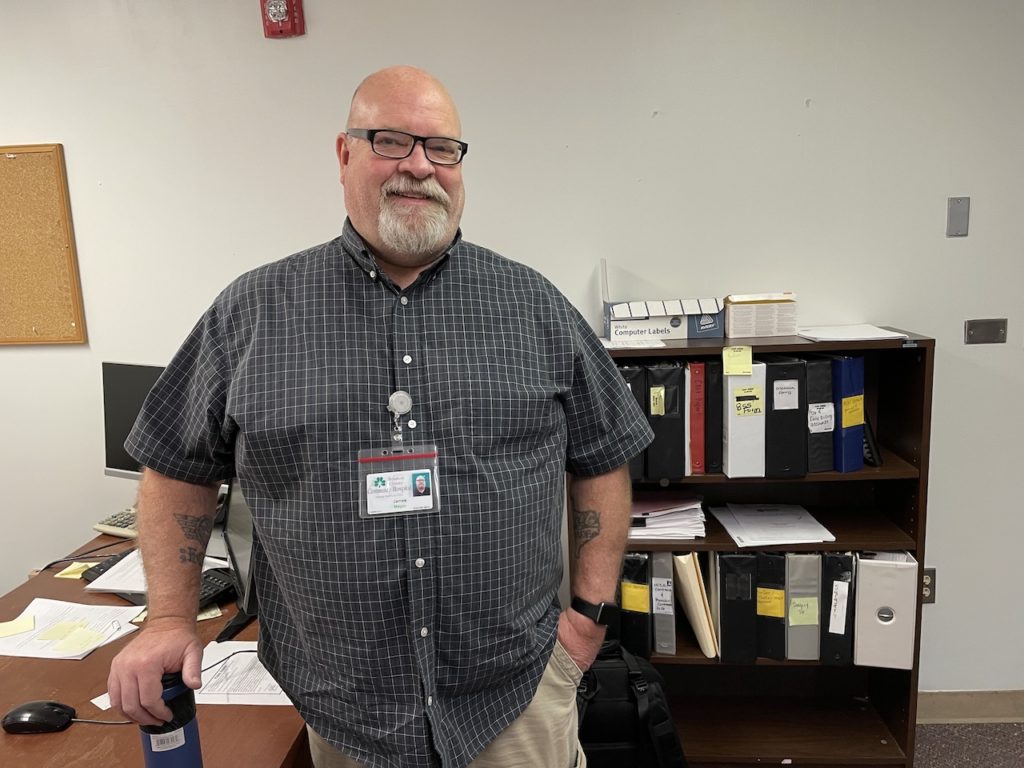

Blake Farmer WPLN News

Blake Farmer WPLN NewsJennifer Warren oversees maintenance at the Houston County hospital, where until recently she didn’t want to go as a patient.

Jennifer Warren, the facilities manager at the Houston County hospital said she’s chosen to make the 70-mile drive to Nashville to receive care instead of using her own hospital. “Don’t get me wrong, I know that the citizens — and I even was one of them — that didn’t want to come here because it was going down,” she said.

Under a previous company, Warren said she wasn’t allowed to make basic purchases to maintain the building — for tools as small as a sander. Now, Warren said she has a budget to make the hospital a place where she and others would actually want to be treated.

“The fact of it is,” she said, “my mind has been changing.”