Lily Porter is standing outside her second-floor classroom as more than a dozen fourth graders file down the hallway.

“Here they come,” she says, waving and giving out pandemic-safe air hugs. “These are my babies.”

Porter is a teacher at Shwab Elementary School in East Nashville. She was part of the first wave of educators to return to school buildings in November, before Metro Schools backtracked on its reopening plan amid a spike in coronavirus cases.

So there’s a big smile on her face as she gives her kids a brief introduction before allowing them inside the classroom.

“You have new seats. You’ve have some instructions on the board. But get some hand sanitizer before you start eating, OK?,” she says. “I’m so happy to see you. Come on in.”

Porter begins the class with a morning message and a few housekeeping rules. She briefs the students on new classroom norms, and the importance of wearing masks and social distancing.

Then, for the first assignment, she asks the kids to share their feelings about being back inside the building. The students respond with mixed emotions. Most are excited. Others say they’re looking forward to the opportunity to “learn better.”

For Porter, however, she’s happy but still nervous being back in the physical classroom.

“I don’t want to scare them. I don’t want to project any fear onto them,” she says. “But I do want to make sure that they’re keeping themselves and me safe too.”

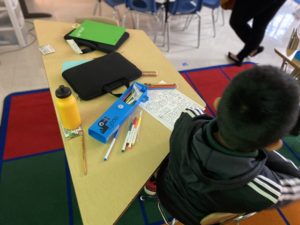

Damon Mitchell WPLN News

Damon Mitchell WPLN NewsPorter welcomed back more than a dozen students earlier this month.

Metro Schools is one of two Tennessee districts that have been mostly virtual since last March. Parents and state lawmakers have criticized the district’s decision. There have also been several school reopening rallies to get kids back into buildings.

Nashville teachers have been caught in the middle of the tense debate, and Porter’s heard the comments directed toward educators who didn’t feel safe returning.

“I think the argument of, ‘Oh. Teachers just want to stay at home in their pajamas and teach from home,’ is such just baloney,” she says. “Because obviously I’m happy to be here.”

Safe to reopen?

Damon Mitchell WPLN News

Damon Mitchell WPLN NewsA student turns to elementary teacher Lily Porter as she briefs the class on an assignment.

According to federal school reopening guidelines provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, schools can reopen in at least some capacity with mask mandates and other mitigation strategies. This is even with high levels of community transmission.

A CDC study on school safety in Wisconsin also found that in-school transmission was unlikely with recommended precautions.

General safety protocols include regularly cleaning, adjusting classrooms layouts to increase space and improving ventilation. For districts like Metro Schools, however, adhering to every guideline isn’t possible. Many school buildings don’t have working windows, and classrooms tend to be small with a lot of students.

These studies, therefore, aren’t black and white.

Damon Mitchell WPLN News

Damon Mitchell WPLN NewsA row of books are shelved in a small section of Lily Porter’s classroom.

“We do lean heavily on what the CDC says, and I think we just try to follow the guidance the best way that we can,” says Sharla Smith, a registered nurse and onsite employee health and wellness manager for the Clarksville-Montgomery County School System. “I can’t tell you whether or not it’s true if it’s in schools. It’s really hard to tell.”

Clarksville public school officials have been applauded by the Tennessee Health Department for their handling of the pandemic. The school district has had an in-person option since the fall. The district has a mask mandate and requires social distancing. They also have a dedicated COVID response team.

For the most part, says Smith, school spread is based on individual communities. She also says that low rates of in-school transmission doesn’t mean people shouldn’t worry.

“There are lives at stake. Because even if it’s not critical for a little person to receive COVID, it may be [for] somebody in their household,” says Smith. “Those things could possibly be fatal to their family members.”

She says the same principle applies to teachers and other school employees.

For Porter, that means even the slightest chance of getting COVID shouldn’t be taken lightly.

“Maybe there aren’t as many teachers who are getting it from schools as folks who are just out and being reckless with their lives and not wearing masks,” she says. “But the teachers who have died are somebody’s wife, daughter or mother. Who knows, it could be me.”

Porter drove an hour and a half to Putnam County for her first vaccine dose. That was before Metro Schools made plans to start vaccinating teachers later his month. She says she would have rather had her second vaccine dose before coming back. For now, however, she’s focused on educating her students.

Damon Mitchell WPLN News (File)

Damon Mitchell WPLN News (File)Lily Porter leads her class to the school cafeteria before recess.