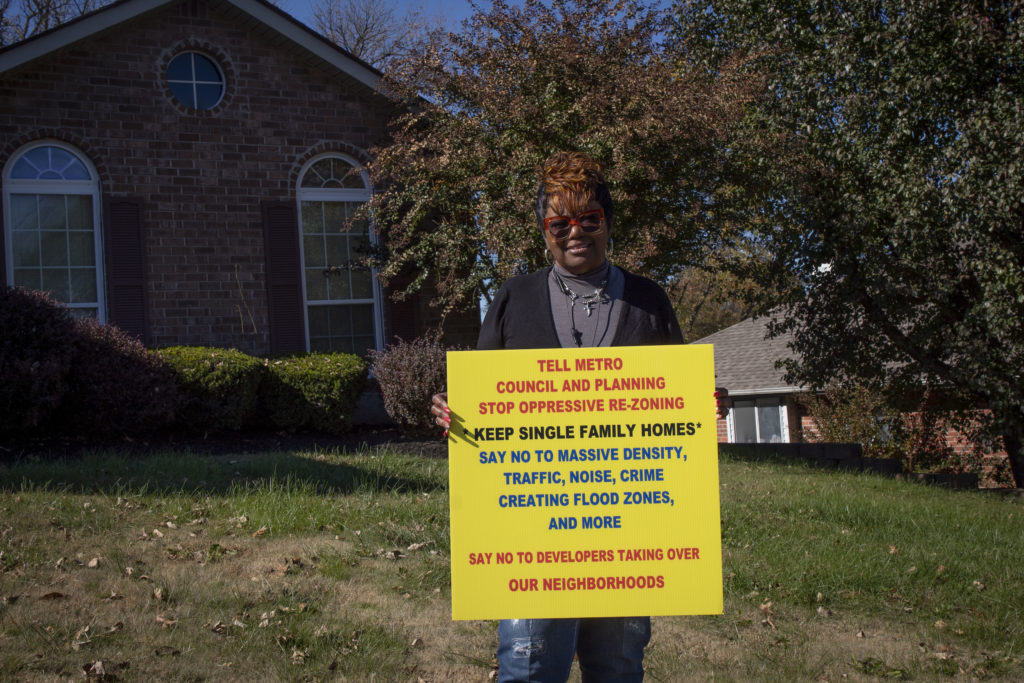

Claudia Wright moved to the Clay Mill Station subdivision eight years ago.

It sits off Ewing Drive, a two-lane street with mostly single-family homes. To Wright, the area signifies a shared vision and commitment to the community.

“You can hear children playing outside,” she says. “It’s a one way in and one way out subdivision.”

Wright is concerned that a proposal to rezone land for a 180-unit workforce housing complex will mean more people and more problems.

The mayor’s housing task force report says the city needs to create over 5,000 affordable units each year to meet the housing demands by 2030.

The proposed area in district two has problems like water runoff.

“I get a lot of complaints from developers about how strict and expensive those requirements are,” Metro Councilmember Kyontze Toombs says. “The developer has engineers, and they study the area and determine what things have to be put in place to prevent or to catch the water from the runoff. So any development you can’t just put something up, and it makes the area worse in terms of stormwater.”

Wright also worries about traffic congestion and how renters could impact the neighborhoods’ culture.

However, she would support the development of homes.

“We have to pay property taxes. We have to pay homeowners insurance. Unfortunately, renters don’t have those responsibilities. They don’t have anything invested,” she explains. “And they do not appreciate the community and the property like we do.” She says this is her viewpoint as a former landlord.

Stigmas are baked in about who renters are and how they live.

This project is for folks making between $38,362 and $76,725 each year — so workers like teachers.

“Part of that goes back to not only the stigma to rental, but the lack of trust of planners and local government saying ‘this is going to be good,'” Tennessee State University professor Ken Chilton says.

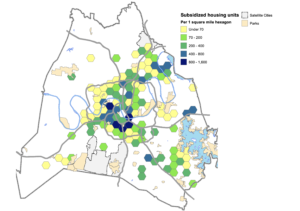

Some Black residents are concerned that affordable housing is mostly going in their neighborhoods.

They’re right. Because of systemic racism land is valued lower and that’s what allows developers a chance to offer housing at a lower rate.

The mayor’s recent task force report shows where subsidized housing is going in the county.

“There is a legitimacy to the claims of the groups,” Chilton says, “that say, ‘And how come it’s always African-American communities that either get the high-end gentrified type stuff that would push us out versus the low-end multifamily workforce marketed housing that really increases densities and doesn’t necessarily increase property values for those who happen to own?’”

Toombs says she thought the project would be perfect for the area since it’s on a major corridor and wouldn’t be visible from the road. She often finds herself in a position of educating homeowners about renters.

“I think you have to walk a fine line with that conversation because as council person, I represent everybody, so I represent the renters, the homeowners,” she tells WPLN News. “And so that’s why in in the projects that I support, I try to address the concerns of everyone as much as I can. I do push back a little bit on the viewpoint of renters, but I’m careful in what I say, because my goal is to facilitate the conversation and not dictate it.”

She says she doesn’t want people to feel like she’s telling them they’re wrong because she’s their representative.

City officials will have to prove they’re distributing projects throughout the county if they want a shot at rebuilding trust.

For the fifth time, the community will get together at 6:00 p.m. Thursday, Dec. 2 at Casa de Dios to discuss the proposal. Next week, the Metro council will consider if they should approve, decline or delay the vote — though the councilperson says she isn’t sure she’ll push for an approval.